When barely sixteen I spent two months with my slightly younger brother Dave hitch-hiking, and often rough sleeping, around Scotland watching birds. We went as far north as the Shetland isle Fetlar to see the snowy owls which bred there, and managed to cadge an overnight lift from Lerwick back to Fraserburgh, on the Scottish mainland, aboard the Nicholas Ellis, a substantial seventy-foot wooden fishing boat (not, we were told, a trawler) used to transport the Shetland catch to market. We were made very welcome, given curtained berths of our own in the stern of the boat, and plied liberally with the same fried food and tea the crew enjoyed. The passage took some sixteen hours, in clear weather with a fresh wind and a lively sea. I recall waking up in the small hours of the light northern summer night and going onto the heaving deck alone, to experience the elements as never before. I little imagined that fifty years later I would have published two books about vessels of this kind, by Gloria Wilson—a lady whose life’s work has been to record, in words, drawings, and photographs, their construction and use, and a culture around them which is fast disappearing.

When barely sixteen I spent two months with my slightly younger brother Dave hitch-hiking, and often rough sleeping, around Scotland watching birds. We went as far north as the Shetland isle Fetlar to see the snowy owls which bred there, and managed to cadge an overnight lift from Lerwick back to Fraserburgh, on the Scottish mainland, aboard the Nicholas Ellis, a substantial seventy-foot wooden fishing boat (not, we were told, a trawler) used to transport the Shetland catch to market. We were made very welcome, given curtained berths of our own in the stern of the boat, and plied liberally with the same fried food and tea the crew enjoyed. The passage took some sixteen hours, in clear weather with a fresh wind and a lively sea. I recall waking up in the small hours of the light northern summer night and going onto the heaving deck alone, to experience the elements as never before. I little imagined that fifty years later I would have published two books about vessels of this kind, by Gloria Wilson—a lady whose life’s work has been to record, in words, drawings, and photographs, their construction and use, and a culture around them which is fast disappearing.

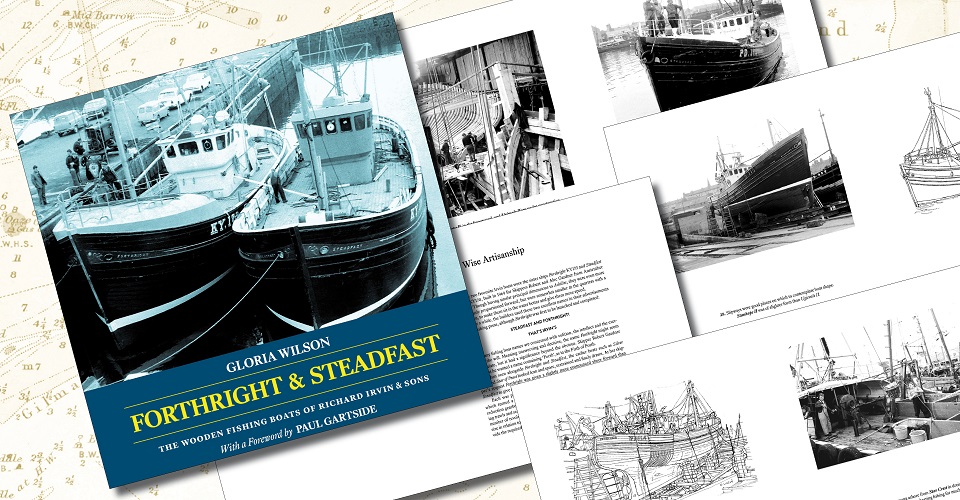

Gloria’s second book for Lodestar, Forthright & Steadfast, is dedicated to one particular yard, Richard Irvin at Peterhead. The Cornish naval architect Paul Gartside, now US-based and a consummate designer and builder of wooden sailing and motor craft, worked on wooden fishing boat projects in his youth, is familiar with Gloria’s work and the Scottish fishing boat tradition, and so proved far better qualified than I could have hoped when I approached him to write the Foreword to her book. Here it is:

In Forthright & Steadfast Gloria Wilson illuminates the work of the Richard Irvin shipyard in Peterhead on Scotland’s east coast between the years 1950 and 1978, when the company ceased new construction. She marks its passing and the end of an era that in my view deserves to be marked and celebrated far more than it is. It is a fact that those of us born in the mid twentieth century have been witness to the final blooming of a thousand-year-old tradition in the British Isles, that of commercial wooden shipbuilding. It has gone extinct in our generation and is unlikely ever to return.

We are not talking wooden boatbuilding here which continues to thrive in a modest way in the world of yachts, adapting as it does so to modern methods and materials. No, what is described in these pages is a different world altogether. In the first place it is a commercial world in which the economic equation of return on investment drives both vessel design and construction. They in turn are a reflection of continual changes in fishing methods, engine power and equipment. Secondly, it is the world of heavy timber construction in which vessels are built on sawn frames of massive proportion cut from grown oak, that is, from the natural crooks of the English oak tree, and are planked with larch, spiked on with galvanised boat nails, the seams caulked with cotton and oakum. It’s a method little changed from that used by the Elizabethan explorers, or by the Royal Navy in the Napoleonic wars, or by the East India company in the age of colonisation. That it survived in the fishing industry long after it had died out in all other areas of marine trade is a remarkable fact.

More remarkable still, at the same time Neil Armstrong was landing on the moon, one could walk into boatyards all round the coast of Britain and see this ancient art being practiced, not out of sentimentality, but because it was still the best solution to the economic equation. In larger vessels wood gave way to steel in the early years of the last century, but steel was slow to find its way down to small and medium size fishing vessels. Fishermen prized the cleanliness and relative ease of maintenance of a wooden boat and the weight distribution in the structure that has so much to do with motion at sea. In the 1970s fibreglass broke through into the smaller end of the commercial sector and began steadily working its way up into the ground traditionally held by wood boats. Caught between the two alternative materials, heavy wood finally succumbed in the last decades of the twentieth century, its demise hurried along by the fishing policies of the European Union. I cannot say for sure that no wooden fishing vessels are being built today in the British Isles, but if they are, they will be the exceptions. The last generation of craftsmen steeped in this tradition, along with the specialist suppliers of grown timber and fastenings, are all sinking below the horizon now. This is what makes this book so valuable and so timely.

Gloria Wilson grew up in an artistic family in Staithes on the Yorkshire coast and it was there that she became interested in the small fleet of English cobles. Later, in nearby Whitby, she first encountered the lovely Scottish cruiser sterned vessels that seem to have cast a spell over her entire working life.

I discovered Gloria’s work in the 1970s as a young naval architect doing stability work on a wooden fishing vessel under construction in Cornwall in south-west England. Having grown up in a boatyard I was familiar enough with wooden boats, but the heavy sawn frame construction used in fishing boat building was a different planet and a revelation to me. I read everything I could on the subject, from the scantling rules of the White Fish Authority which prescribe the dimensions of all structural members, to Gloria Wilson’s books Scottish Fishing Craft and More Scottish Fishing Craft, and her many articles in Fishing News, as well as the writings of the great Ayrshire builder Alexander Noble. There they are on my bookshelf now in a well used section that includes the standard texts on fishing vessel stability—a reminder of a very happy period in my life

It was no coincidence that my focus at that time was north of the border. It was clear that the Scots were on the leading edge of things. It was the Scots who were pushing the limits of the length/beam ratio, building boats wider and with greater freeboard than ever before. How it must have distressed Gloria to see her beloved cruiser stern give way to transoms, but that was the trend—and still is. Increased engine power and the explosion of hydraulically operated equipment changed the picture too, adding loads to the structure never envisaged by the authors of the White Fish Authority rules. In response the Scottish builders were incorporating ever more steel into their vessels—engine beds, bulkheads and deck support knees. Gloria’s description of the Irvin shop filled with a mixture of smoke from the welders and steam from the steam box used to soften and bend the planking captures the era perfectly.

Another milestone she notes is the imposition of stability regulations and assessment both before construction begins and after launch—this as a direct result of the development of computer software in the early 1970s. No longer were the builder’s model and the loftsman’s eye sufficient warranty of seaworthiness, as they had been for all previous generations. From here on every step of the process would bear the regulator’s stamp. That was a big change, and while probably for the best, one feels for those quiet competent tradesmen Gloria so admires—men with more intuitive knowledge than an army of mathematicians.

The best parts of the book from my point of view are the descriptions of the method used at Irvin’s to evolve their designs from one boat to the next. Her portrait of George McKechnie the loftsman is priceless. I could have wished for much more of that kind of conversation with the tradesmen in the yard to better understand their methods and equipment. But one cannot have it all. Gloria’s vision is a wide one that includes the development of the port of Peterhead, the skippers and their landings as well as her experiences going to sea in the vessels she so loved.

Gloria Wilson truly belongs in the tradition of the folklorists—individuals moved initially by the discovery of beauty in the commonplace who are then compelled to understand and record what they find. In doing so they leave a legacy of riches for future generations. In that sense she keeps company with the likes of Cecil Sharp and Alan Lomax, or in the world of boats, Phillip Oke and Howard Chapelle. One hopes her example will spur others to similar effort, for the capturing of culture and local knowledge before it slips away is always a noble pursuit.