Somehow, and to his incredulity, I had never read an Arthur Ransome book when Peter Willis approached me with Good Little Ship. Nancy Blackett, the real-life original of the Goblin in We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea, was a familiar sight on the East Coast and clearly much loved, and so must be that book, which I sat down to read forthwith. I’m told it’s a very different read from the other Ransome tales; it had me in an emotional armlock from cover to cover, so even if you think the Ransome books don’t appeal (I felt this myself, with no good reason) We Didn’t Mean… is a surefire point of entry for readers of all ages.

Somehow, and to his incredulity, I had never read an Arthur Ransome book when Peter Willis approached me with Good Little Ship. Nancy Blackett, the real-life original of the Goblin in We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea, was a familiar sight on the East Coast and clearly much loved, and so must be that book, which I sat down to read forthwith. I’m told it’s a very different read from the other Ransome tales; it had me in an emotional armlock from cover to cover, so even if you think the Ransome books don’t appeal (I felt this myself, with no good reason) We Didn’t Mean… is a surefire point of entry for readers of all ages.

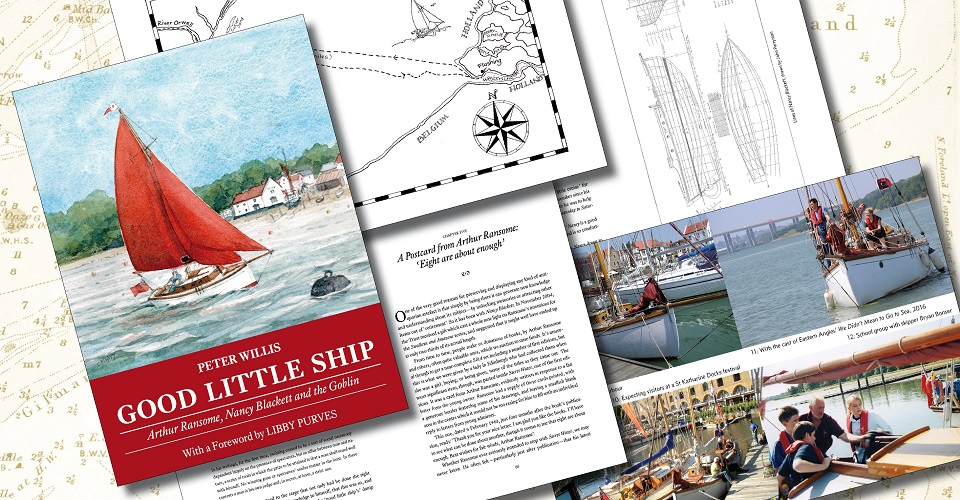

Peter is founder and President of the Nancy Blackett Trust which preserves the unassuming little yacht for the enjoyment of Ransome-lovers who perhaps have no boat of their own, and his book combines the boat’s own story, not without its dangers, with a fascinating analysis of Ransome’s leading character John, and by extension Ransome himself. Author, broadcaster and sailor Libby Purves has distilled the meaning to so many people of Ransome’s book, the Goblin, and the Nancy Blackett in her foreword to Good Little Ship:

We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea was for me, and countless others, the spark of a love affair. As a child I was given other Arthur Ransome books, and mildly enjoyed the Swallows’ and Amazons’ adventures in the Lakes, and the muddy world of Secret Water. Later, already having sailed the Atlantic myself as a yacht crew and fallen in love with the tall-ships races, I quite enjoyed the treasure-hunting of Peter Duck and the fantasy of Missee Lee.

But We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea is different: neither children’s play on calm waters in reach of rescue, nor a piratical fantasy either. It stands alone because every stage of the Goblin’s accidental voyage to Vlissingen is deliberate, possible, thrillingly solid. It could happen. Every danger on the way is real and familiar to anyone who sails our British waters in a small boat: seasickness, sandbanks, rising wind necessitating a grit-teethed, panicky reefing operation. There are big ships, worries about navigation lights, and that uncertainty, so familiar before the days of GPS, as to where you actually are when dawn breaks.

John’s anxiety about salvage and grounding is rational, not a child’s bogeyman fears. The responsibility he takes for his siblings, and their various fear, trust and gallantry, make reading it at times intensely moving. When, rushing through the dark at the helm of the little Goblin, the eldest looks below to see her sleeping crew, what fills him is universal—a sense that every lone night-watch keeper in dark waters can feel with him: ‘a serious kind of joy’. Who, among small-boat offshore sailors, does not remember the night when ‘for the first time crew and ship were in his charge, his alone’? And the serious joy of it?

I read the book when I had just started sailing, finding myself—after putting a small-ad in Yachting Monthly—at the bidding of a random set of skippers, longing to learn, enamoured of every sail and sheet, entranced by the timeless practicalities of rope and canvas. At work, as a young Today presenter, I would fill in the duller moments during ‘Thought for the Day’ doodling layouts of possible boats on the edge of the script. The Goblin was always the matrix, the basis of any ideal boat: her origin, as this engrossing book celebrates, was dear Nancy Blackett, which still sails our East coast waters.

When, with my then boyfriend (now husband) we bought our first boat it was a 26ft Contessa: modern in comparison to Goblin but with the same long keel and squared stern, the graceful hull and simple tiller that we instinctively trusted. We polished our brass lamps, cherished the woodwork of the little cabin, and felt the way the children do in the book: trusting a good little ship. We knew that while we were amateurs the boat was a professional, her design refined over generations to take the seas with grace.

Later came other boats, bigger ones, but always we eschewed the modern wide, caravan-like, light-finned yachts and the sleek racers in favour of solidity, the narrow sobriety of handholds, heavy keels and a shape made gracious by centuries of knowledge. Thus Goblin and Nancy Blackett helped to shape our sailing. And for me at least, on many a night passage with an unwelcome forecast, the spirit of the book was a kind of comfort. I have looked down into a lamplit cabin and seen my children sleeping, and my husband rolled up off-watch in a blanket but with boots still on, and let them all sleep longer. That serious joy means looking forward to raising the first shorelights alone and waking them to the good news, as pleased as if you’ve lit them yourself. It is a joy born of responsibility, of competence, of rejoicing in the boat herself, as she cuts through the waves and leans to the slope of the wind.

Adrian Seligman wrote of far bigger ships, the old square-riggers on the great grain race, ‘a sailing ship at sea is one of God’s most patient, yet most steadfast and courageous creatures’. A little yacht, a humble yacht like Goblin, has its share of that glory. And, as Seligman adds, ‘those who live with her, who watch her day by day… these people learn from her, in time’. We all have.