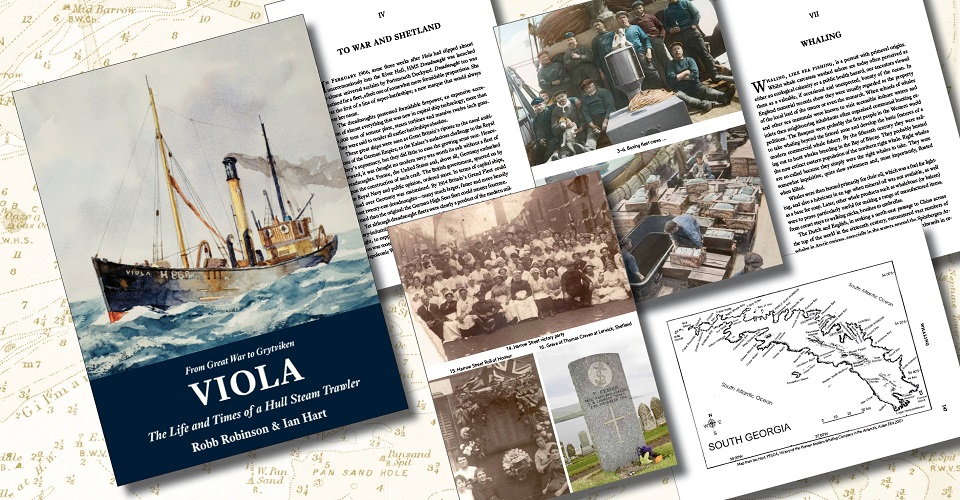

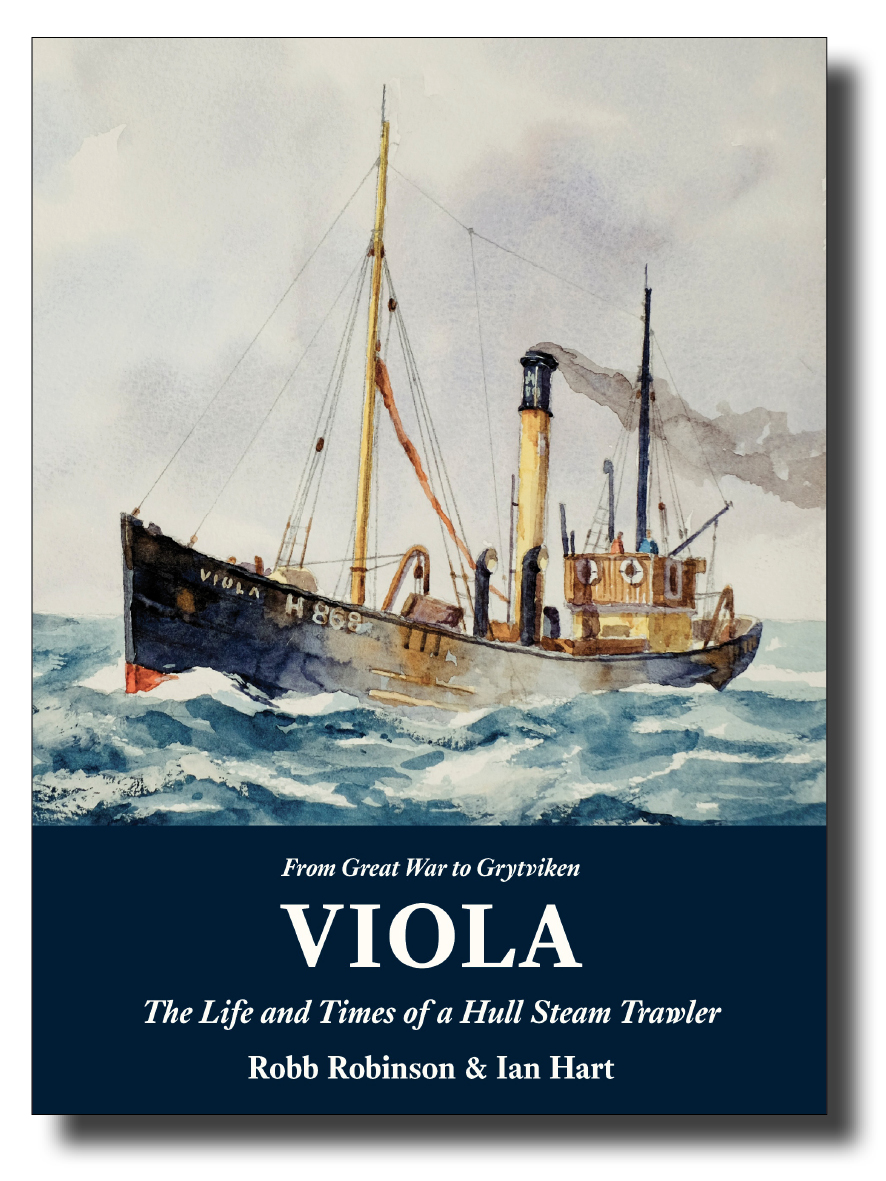

The Albert Strange Association (bear with me), in which I am heavily implicated, held its Annual General Meeting in Lincoln a few years ago, and our very engaging guest speaker was Dr Robb Robinson, a maritime historian at the University of Hull. His subject was Viola, the last surviving pre-World War I Hull steam trawler; surviving only because she escaped the scrapyard by migrating to the sealing and whaling industries in the far south, where she remains abandoned today in South Georgia, having narrowly escaped scrapping again, by the Argentinians in 1982. I suggested to Robb there must be a book in this, and he responded that indeed there was, but he could find no publisher interested. Well I was, and Viola has become one of our best-selling titles. There is now a lively campaign to bring the ship back to her home port for the first time since 1914, with Hull West MP and ex-Government minister Alan Johnson at its head. Below, Robb sets the scene for an extraordinary piece of maritime and social history:

The Albert Strange Association (bear with me), in which I am heavily implicated, held its Annual General Meeting in Lincoln a few years ago, and our very engaging guest speaker was Dr Robb Robinson, a maritime historian at the University of Hull. His subject was Viola, the last surviving pre-World War I Hull steam trawler; surviving only because she escaped the scrapyard by migrating to the sealing and whaling industries in the far south, where she remains abandoned today in South Georgia, having narrowly escaped scrapping again, by the Argentinians in 1982. I suggested to Robb there must be a book in this, and he responded that indeed there was, but he could find no publisher interested. Well I was, and Viola has become one of our best-selling titles. There is now a lively campaign to bring the ship back to her home port for the first time since 1914, with Hull West MP and ex-Government minister Alan Johnson at its head. Below, Robb sets the scene for an extraordinary piece of maritime and social history:

Deep in southern latitudes, in a desolate corner of Cumberland Bay on the east coast of the sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia, hard by the rotting quays of the abandoned whaling station of Grytviken and almost within a stone’s throw of the grave of Sir Ernest Shackleton, lie three forsaken steam ships: rusting remnants of our industrial past, unique survivals from a vanished age of steam at sea. Far from any main shipping lane, the isolation of their anchorage has helped them avoid the scrap-cutter’s torch.

Their refuge is certainly remote. Set amongst savage South Atlantic seas, South Georgia ranks high on any list of far-flung places of our earth. A dramatic glacial wilderness of around 120 miles in length, yet no more than twenty or so in width, it lies on the Scotia ridge and can only be reached by ship after a voyage of some 800 miles from Stanley in the Falkland Islands.

A haven for albatross, skuas, petrels and countless other seabirds, its vast snow-streaked peaks of Alpine proportions rise steeply, almost straight from the sea, above colonies of millions of penguins and the herds of huge elephant seals that haul themselves ashore in sparse tussock-strewn bays for a few months each year to give birth. There are no towns, or even villages, only a string of derelict whaling stations that cling where they can to the shores beneath spectacular ice-clad mountains and great glaciers along the island’s eastern coast. Although visited by passing cruise ships, much of the island is almost, but not quite, devoid of any permanent human presence. King Edward Point, across Cumberland Bay from Grytviken, is the centre of the island’s administration and today home to a sophisticated fisheries research laboratory.

Even when whaling operations were in full swing, much of the wider world knew little of South Georgia, let alone had any idea where it was; except, perhaps, on the two occasions when dramatic events brought it briefly to the attention of the international media. Back in 1916, Ernest Shackleton reached the island after an 800-mile voyage across huge seas in a small open boat, from Elephant Island where the crew of his ill-fated Antarctic expedition was marooned. His party scrambled ashore in King Haakon Bay on the west coast. Although exhausted, Shackleton and two companions had no choice but to become the first people to traverse the glaciers and uncharted mountains of the island’s interior in order to reach the comparative safety of the Stromness whaling station. Shackleton subsequently rescued all his crew from Elephant Island but was later to die of a heart attack aboard his ship, Quest, in Cumberland Bay on returning to South Georgia, en route for the Antarctic again in 1922.

Some sixty years after Shackleton was buried in Grytviken’s cemetery, South Georgia hit the headlines once more. On a cold and wet morning, this time in March 1982, a group of Argentine scrap metal merchants were landed by the naval auxiliary Bahía Buen Suceso at Leith Harbour, a few miles from Cumberland Bay. Their remit was to cut up the rusting equipment that littered the old whaling stations, and the three old ships left in the waters of Cumberland Bay.

Yet something was not quite right about the Argentines’ arrival. Diplomatic protocol and international law required that the Bahía Buen Suceso should not have disembarked people at Leith Harbour before visiting Cumberland Bay and reporting for Customs and Immigration Clearance to the official British Magistrate, a scientist resident at the British Antarctic Survey Base on King Edward Point. This they conspicuously failed to do and instead raised the Argentine flag at Leith Harbour. Thus began the incident that arguably opened the Falklands War.

The British Government, caught off guard by the subsequent escalation of a long-simmering conflict, had less than one hundred marines and the survey vessel HMS Endurance in the South Atlantic with which to defend the Falkland Islands and their Dependencies from a full-scale Argentine invasion. Within weeks, the Falkland Islands were in Argentine hands after a spirited defence by the British marines around the Governor’s House in Stanley. South Georgia was taken a little later when Argentine soldiers reinforced the original landings at Leith Harbour, but not before they faced a fierce firefight around Grytviken with just eighteen British marines, who eventually surrendered to an overwhelmingly larger force.

History records that these Argentine successes were of short duration. A British Task Force was quickly assembled and within days had set sail for the South Atlantic. A few weeks later South Georgia was back under British control after a series of actions in which UK military helicopters disabled the submarine Santa Fe and landed Special Forces on shore. The British Task Force’s recapture of South Georgia was a precursor to retaking the Falkland Islands via San Carlos Bay, Goose Green, and battle on the heights above Stanley.

For a few short weeks events on South Georgia attracted world attention. Cumberland Bay was briefly a hive of unaccustomed activity, being visited by various requisitioned vessels including the liners QE2 and Canberra. Today a few remnants, including the wreckage of an Argentine helicopter brought down by British troops, remain around the island as reminders of the war.

International interest soon vanished. Though the dispute over the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands and the Dependencies continues to this day, South Georgia, the forsaken whaling stations and the old ships slipped back into their accustomed obscurity. Much of the island remains largely untouched and unspoilt, a haven for seabirds and seals—an immense natural sanctuary—although the old whaling stations have steadily deteriorated, their scrap metal, which had ostensibly lured the Argentines back in 1982, continuing to rust away.

On another grey and grainy morning back in February 1906, almost seventy-six years before the landings at Leith Harbour, the cold, wet quaysides by the Humber around St Andrew’s Dock in the great seaport of Hull were also alive with activity. Light showers and occasional flurries of sleet and snow dusted the docksides as close on fifty steam trawlers prepared to take leave for the North Sea fishing grounds. This was the first full sailing of the new Hellyer Boxing Fleet.

So-called boxing fleets were an early form of industrial fishing. Their name came from the boxes in which the trawler crews packed their newly caught fish. The ships in these fleets worked far from port for weeks on end. Most days fast steam cutters reached the fleets from London, and the boxes of fish were transferred from trawlers to cutter by open rowing boat in every kind of weather. Once laden with all the trawlers’ catches, these cutters then dashed for the Thames, at high speed through all sorts of sea, past empty sister ships steaming back out to the fleet. Cutters, trawlers and trawlermen: all played their part in a seemingly unending struggle to service Billingsgate Market and satisfy London’s almost insatiable demand for fresh fish.

Three fleets of boxing steamers already hailed from Hull. These were known respectively as the Gamecock, Great Northern and Red Cross fleets. But Charles Hellyer, Hull’s leading trawler owner and Managing Director of the Hellyer Steam Fishing Company, thought there was room for another such venture, and in September 1905 he announced plans to build a new North Sea boxing fleet from scratch. The scale and pace of Hellyer’s project was staggeringly ambitious, even for an Edwardian British fishing industry that led the world. Almost £450,000 worth of orders with tight delivery dates were quickly placed with, and then turned out by, shipyards on the Humber, Tyne and Clyde. Whilst the earlier boxing fleets had been built up over several years, this one was ready to sail within five months.

As dawn broke on that morning in February 1906, the crews were already trickling through the wide wet subway below the busy railway that separated the dock from the warren of red brick streets and terraces on the southern side of Hull’s Hessle Road district. For a time, the trickle approached a torrent as men, young and old alike, dodged around crowded carts, rullies and railway wagons full of fish, and hurried past busy barrow-boys who were bustling boxes and barrels beneath the gaunt structure of the fish market. All headed for the lock pit area, anxious to watch the spectacle and catch a last glimpse of family and friends going to sea.

The district’s women were no less interested or anxious about all that the fleet’s sailing entailed, but few watched. Women might welcome you home from the sea but it was considered bad luck on Hessle Road to be seen off by a female; farewells had already been made in the crowded ‘sham fours,’ the terraced houses, across the railway track. Meanwhile, men and boys gathered on the windswept quays below the big skies by the broad, brown mud waters of the Humber estuary to watch the fleet sail. Because of the sheer numbers of vessels involved, some trawlers had already passed through St Andrew’s lock gates and out into the Humber roadstead by the time crowds gathered. Almost every vessel in the fleet had a Shakespearian name—Hellyer named all his ships after the Bard’s characters— and indeed it seemed that an armada of almost Elizabethan extent was taking leave of the port.

The sailing of a full boxing fleet was a far from common occurrence, for these fleets might remain at sea for years. Individual trawlers returned to port every five or six weeks when coal, provisions and crews were exhausted, but as they left the fleet other vessels took their place, refuelled, revictualled and ready to resume their unrelenting trawl. Unless weather conditions were extremely dire, these fleets kept a constant presence on the far-flung North Sea grounds, trying to meet the demand for fish, not only of London’s Billingsgate but also of countless other fish markets across the country. By the Edwardian epoch white fish was a working class staple. The fish and chip shop had emerged in the previous century to help sustain Britain’s rapidly growing towns and cities; fish and chips were the first fast food of the new industrial age, almost a maritime McDonalds but without the corporate dimension.

No one owned the fish these fleets sought; the rich grounds they worked had never been appropriated. The trawler crews pursued a common—if fugitive—maritime resource. Deep-sea fishermen were—and are—amongst the last people in the world to hunt for a living. Sea fish may be theoretically free for the taking but the real costs of catching them have always been considerable, to be counted not only in terms of capital expended on vessels and gear but also in pounds of flesh and blood—in fishermen’s lives. Throughout the twentieth century, fishing remained Britain’s most dangerous industry. Statistics suggest it was four times more dangerous than coal mining. Those whose business was steam trawling often toiled in great seas, far from the comforts of family and home, in cold grey waters and every sort of weather to haul a harvest from the deep. They faced the full force of both natural and human agents of destruction. In just twelve years, between 1906 and 1918, no less than twenty-two of the fifty or so trawlers built for this Hellyer fleet were lost, either to the sea or to enemy action in the Great War. Bereavement remained an all-too-common burden for the families of fishermen throughout the twentieth century.

In much the same way as South Georgia’s whaling stations have been abandoned, Hull’s once proud St Andrew’s Dock—periodically in the media spotlight when at the wrong end of a series of Cod Wars with Iceland between the 1950s and 1970s—has also slipped into an obsolete obscurity, long since forsaken by Hull’s fishing vessels, a fleet no longer even a shadow of its former self. Even before the Falklands War this dock, once home to the greatest distant-water trawling fleet in the world, had also been deserted, partly filled in, and many of its surrounding buildings left derelict or demolished, bulldozed into oblivion during the 1960s and 1970s like so many of the adjacent terraces. Huge swathes of the strong Hessle Road community, of a distinct industrially maritime way of life, have been dispersed to the winds.

All physical trace of the once proud Hellyer fishing fleet had disappeared many years before the dock’s decline; with one exception. Amongst the multitude of trawlers taking the tide in the Humber on that distant day in 1906 was the newly built steamer, Viola. Whilst all her sisters have long since been scrapped or else sunk in storms or war, this one seemingly insignificant craft has survived against all the odds. In 1982, this self-same vessel lay in Cumberland Bay, awaiting the Argentine scrap metal merchants’ cutting torch. Today, accompanied by the former whalers Albatros and Petrel, she still lies at the ruined township of Grytviken, South Georgia, part of a ghost fleet from a forgotten age.

Throughout most of a career which encompassed almost the entire length of the long Atlantic, through both war and peace, this little ship, this former Hull trawler, remained an everyday working vessel, just one of many apparently mundane, most certainly unsung, craft used by mariners of all persuasions to earn their living in a variety of ways across the world’s wide oceans.

Unlike the mighty HMS Dreadnought which was launched three weeks later, Viola was built not for fighting but for fishing, for the profitable and unending task of taking fish for the London market; but the outbreak of the Great War in 1914 changed all this forever. Hastily requisitioned and armed by the Admiralty, the little ship and her crew of fishermen sailed off from Hull straight into the fogs and uncertainty of a grim war at sea, and to more than four years of voyaging through waters infested with U-boats and mines. HMT Viola, as she was by then known, steamed thousands of miles patrolling Britain’s maritime front line, far more than any single dreadnought, and her crew had numerous engagements with the enemy; the little armed trawler survived everything the enemy and seas could throw at her. But the return of peace took her in new directions, to different waters, and Viola has yet to return to her home port from that Great War voyage.