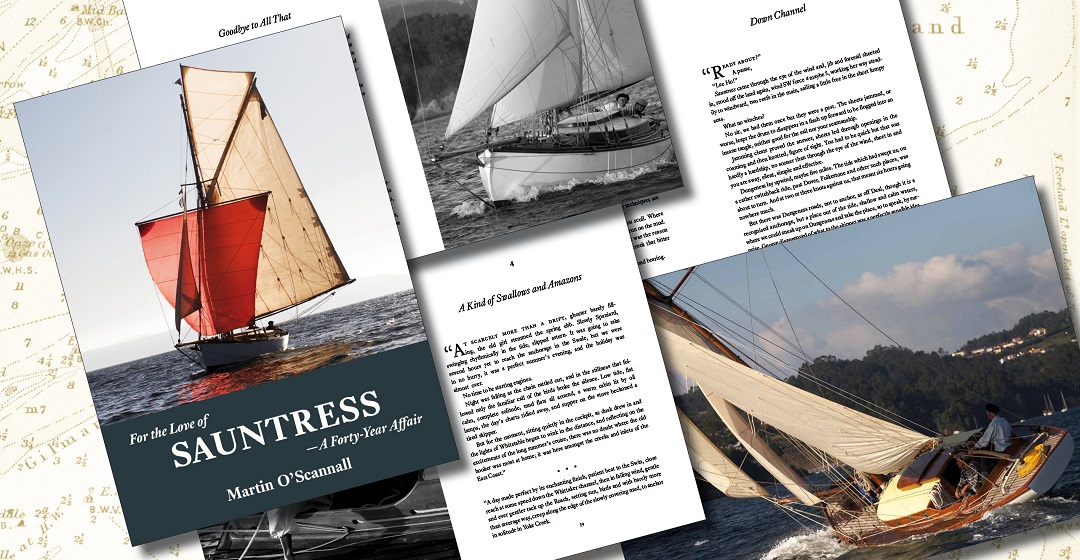

Martin O’Scannall has enjoyed a love affair of more than forty years with his 1913 gaff cutter Sauntress, beginning with her rebuild and culminating in the glories pictured here. Below is his account of her sojourn in a boatyard at Brentford on the Thames in west London, in the early 1970s:

A lovely Irish expression that one, in full “seven brothers and all handy with a toolbox,” quoted in Sneem, Kenmare River, County Kerry; but we were not there yet, not by a long chalk.

Instead we were in the seedy purlieus of West London, Brentford Dock to be exact, one of those havens which had escaped the developers. For behind a high wall lay John Woolley’s little empire, a boatyard, the boats in question being narrow-boats with their floating gypsy-caravan livery, and beyond that the greenery of Syon Park, from which the screech of an invisible peacock could occasionally be heard.

And the lap and gurgle of the Grand Union Canal or, more like, the occasional burp, as something nasty rose from the depths. For only by the wildest stretch of the imagination could this be called a marine environment; but at least there was water.

And here, very much in bits, was Sauntress, victim of a particularly bad attack of gleeful destruction, a bare hull open to the skies, her owner slightly aghast at the enormity of the deed.

But the destruction, though brutal, was necessary.

A hogged sheer is no thing of beauty so the first job was to remedy that. A bare hull, as Sauntress now was, is a relatively flimsy thing. A jack, or more correctly in this case an Acrow prop, exerts enormous power, quite enough to force the topsides back to something approaching their original position. The rest can be, and in this case was, done by planing back the irregularities in the sheer. Now Sauntress once again had a sheer sweet to the eye.

To keep it that way, six pairs of sawn oak frames supplemented her obviously inadequate steamed timbers. Working oak with a pruning saw, fitting, refitting and refitting again until the bevel was perfect, was not a quick job but it would not be done again, so it had to be right. And manifestly was right, for they have never moved since.

The next step was to attack the tenderness. Here the keel, which was iron, was dropped six inches and the gap filled with concrete. This slightly eyebrow-raising approach looks less outlandish when one considers that concrete was even, if not especially, used internally in quality work, witness Claud Worth’s Tern III. In any event it stiffened the boat up and so, in a subsequent refit and a moment of relative prosperity, the old iron keel was removed, recast in lead and refitted minus the concrete.

That done, the more pleasant task of recreating Sauntress as I wanted her to be in my mind’s eye could begin. For this was no faithful restoration of the original, except Wright’s lovely hull. Instead what kind of cabin, what kind of interior layout, what sort of deck, what kind of cockpit, were simply a matter of what would work best, be strongest, and look the part. And look the part meant be in keeping with a yacht of Sauntress’ age and period.

Strength came from new oak carlins, tie-bolted to the beam shelf, massive lodging knees bolted to the main beam and carlins forward, and two new oak beams at deck level aft, where the cabin was to divide from the cockpit.

More strength came from what might be called a composite construction: steel in a wooden ship in the shape of a long steel girder across the floors, longitudinally, with web frames welded on and bolted to the new oak frames, the whole treated against corrosion.

Before a deck could be laid a decision had to be made on what kind of cabin. Not too high, for the quest for standing headroom had produced the ugly doghouse, now consigned to the rubbish. Nor necessarily did it have to be the conventional rectangular box. So the decision was made that the forward end should be rounded, New Zealand yacht style (of the period) on the basis that it was pretty, and more spuriously that it offered less resistance to a wave breaking aboard.

That was built, in teak. The decision to use teak was simply that it was the best timber available, and by best is meant the most durable, pleasant to work and pleasant to the eye.

The deck was more problematic. Almost all restorations or rebuilds use a plywood sub-deck, but I dislike ply and questioned the rigidity of the material in a wooden hull, which by its nature flexes a little in a seaway. So instead Columbian pine, which is extremely light, was laid as a sub-deck. This was fastened with silicon bronze grip-fast nails, and splined. A liquid rubber compound was painted over and a teak deck laid over that, screwed down with marine grade stainless steel screws, plugged.

The scantlings of the teak were such that it could wear over the years without distortion. This deck was not swept as, say, in a Fife boat, but laid straight, which I prefer. It gives a touch of the workman-like or sinewy strength which is the hallmark of Sauntress. It has lasted some 40 years and looks as handsome as ever.

The first cockpit was less of a success as, amongst other things, a large and heavy Coventry Victor single cylinder diesel engine had to be accommodated under the bridge deck; but when that, and its successor—a Japanese engine—were removed and auxiliary power dispensed with, a teak, once again self-draining, cockpit was installed, with a small well which ensured that if a green sea did come aboard, as happened once, the water could drain safely away. Teak washboards replaced cabin doors.

The boat is sailed single-handed or two-handed, so when it came to fitting out the interior she would need to sleep two, or very occasionally three. She was to have a good galley, and a separate chart table and seat for chart work, and once again she had to look of the period, something of the Edwardian yacht. (That incidentally was one reason for preferring the splined sub deck, no expanses of white painted plywood to stare at from one’s bunk, but instead a proper deckhead.)

She also had to accommodate a six-foot crew in comfort when he or she was sleeping below. That meant a settee berth in the main cabin of six feet six inches. For this and quite a few other details I had Donald Street’s The Ocean Sailing Yacht to thank. For I had plans for little Sauntress when I was done.

Thus, the layout as you enter the cabin is as follows. To port is the chart table and navigator’s seat. All internal joinery, unless otherwise specified, is varnished mahogany, in places inlaid with ebony, an expensive and strange wood, but undeniably handsome. Next came the 6ft 6in berth, extending when needed to a double, ending conveniently under the main beam, and separated from the forward part of the vessel by a tongue-and-groove cream painted pine bulkhead. Above is a fiddled shelf for such things as the Walker log, binoculars and GPS, and under the navigator’s seat lives the sextant.

Opposite the navigator, with small folding seat set into the teak steps, is the galley: double sink, Taylor’s stainless steel oven, general galley stowage. Beyond that, and departing from the norm, is a settee, with octagonal swing table, beyond which a sideboard, and facing the main bunk a charcoal stove. Glasses (whisky) and bottles stow behind the settee, and the sideboard houses the barograph and main cabin oil lamp.

This has the inestimable twin advantages that it can be turned low, for sailing at night, and to keep the chill off the air at anchor. Electricity is kept to the minimum, powered by solar panel and used for the chart table, galley, navigation lights and compass light. This arrangement means that the navigator does not disturb the sleeping crew, and the cook disturbs neither.

Forward and to starboard is what has become the owner’s bunk, private and undisturbed there, with the hanging locker and heads opposite, and right up forward, stowage for sails.

This, approximately—for some of the changes came later—was the layout and structure of the yacht as she emerged from John Woolley’s yard after twelve years. And in this form she has been sailing ever since (save the discarding of the engine which will be discussed later).

Her rig is the classic gaff cutter arrangement, with topsail and increasing large sail wardrobe, with Wykeham-Martin furling gear on jib and foresail, and peak and throat halyards led back to the cockpit for ease of handling when single-handing. She now also carries a square sail and yard, the latter permanently aloft and the former sent up on three halyards. Claud Worth describes this arrangement in detail in Yacht Navigation and Voyaging.

We were ready to go back to sea.