Someone, somewhere wrote that George Millar was incapable of writing a dull sentence, and never was that more true than in his three books of sailing memoirs. Oyster River, set in the Morbihan in Brittany, and Isabel and the Sea, relating a voyage through the French canals to the Mediterranean in the aftermath of war, have been reissued in recent years by Dovecote Press, but A White Boat from England, describing a voyage around France and Iberia to the Mediterranean, had been out of print for many years until we reissued it. Peter Bruce, sailor, writer and author of Adlard Coles’ Heavy Weather Sailing, kindly contributed this Introduction to it:

Someone, somewhere wrote that George Millar was incapable of writing a dull sentence, and never was that more true than in his three books of sailing memoirs. Oyster River, set in the Morbihan in Brittany, and Isabel and the Sea, relating a voyage through the French canals to the Mediterranean in the aftermath of war, have been reissued in recent years by Dovecote Press, but A White Boat from England, describing a voyage around France and Iberia to the Mediterranean, had been out of print for many years until we reissued it. Peter Bruce, sailor, writer and author of Adlard Coles’ Heavy Weather Sailing, kindly contributed this Introduction to it:

Truant was a sensible choice for George and Isabel Millar’s first vessel. She was hefty, workmanlike, equipped with powerful engines and allowed Isabel to think of her as her home, it being a delicate matter for a man with an inclination for sea-going to entice a new wife to accompany him. Luckily for George, Isabel took to yachting like a bee to nectar. A half Spanish, half English lady with rare courage, she showed no fear on horseback, or on the sea. Not for her a ritual of safety measures: she was more interested in exploration and, as the daughter of a diplomat, showing the flag, and she was happy to meet any challenge head on.

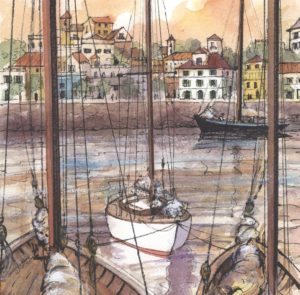

George and Isabel must have studied the passing yachts from Truant in 1946 as they progressed from England to Greece through the canals and the Mediterranean [Isabel and the Sea, Heinemann 1948, reissued by Dovecote Press 2006]. The appearance of a vessel became important to them and they came to appreciate long overhangs and a graceful sheer line. So a fast, close-winded vessel with low freeboard and more than a touch of elegance must have seemed the appropriate way to go, and the 46ft Serica was just that. She had the breathtakingly elegant lines of Robert Clark, who still is one of the most aesthetically admired yacht designers in the world.

Isabel was able to point out Serica with pride when at her berth, not only on account of her lovely shapely looks, but also because at that time just after the war few people owned yachts, and those that did seldom ventured further than their home waters. One can feel George and Isabel’s pride of ownership when George, who had studied architecture at Cambridge, gives a summary of the other English yachts in comparison to Serica. Clearly George took a close interest in naval architecture as well as giving his emphatic opinion on sundry buildings that they encounter.

One soon becomes captivated, as one always is, by George’s unusually acute powers of observation and his ability to ascertain and record exactly what was going on at every stop. Surely only George could have established exactly why the troop of schoolgirls at the rue Oudinot in Quimper needed an escort of no less than two mistresses and eight policemen, and could then relate the feud that caused it in graphic detail? When George takes his reader bullfighting we can clearly visualise the fighters and practically smell the bull. When we get transposed to Dorset we feel more than a whiff of the reality and excitement of foxhunting—poor brave Isabel , though badly damaged when her horse failed at a jump, had no thought for her own predicament, only the other riders—George makes us feel that we are right there, in the thick of it. No wonder, when before the war and working as a journalist for the Daily Express, young George soon came into Lord Beaverbrook’s inner circle. He even tells us individually how the fashionable folk of Cascais dispose of their cocktail sticks.

One of the joys of George’s colourful prose is that we share his innermost thoughts, even to what kind of figure he would like for his husband if he had been born a woman; and he shares with his reader the rather personal confidences of his acquaintances, such as why the Spanish prefer to shave in late evening… indeed George is fond of throwing in the occasional shocker. He is also fond of occasional long involved sentences, for example his description of Glasgow trams employed a sentence running to twenty lines, and there is so much intriguing detail within that we forgive him, and may even choose to read this massive sentence twice or more.

As befitting a war hero and his wife George and Isabel were well-connected, and it is no surprise that they met the King and Queen of Spain, as well as three Admirals. It becomes apparent that they have a gift of making friends, as well as being able to distinguish sincere, kind and modest people from their more pretentious fellows. Amusingly George avoids making any personal remarks when he meets Don Juan, King of Spain. Almost everyone else he meets is made game for richly spiced remarks about their appearance and behaviour. Persistent offenders earn a nickname such as ‘The Bluebottle’. On the other hand those who come to help George and Isabel, he having completed their word picture, are rewarded with generous praise and even have their photographs published. One wonders how many of George’s rather frank comments got back to their subjects…

George repeatedly pleads inexperience in yachting matters while others deny him the luxury of such an excuse. The fact was that both of them were at risk in matters of seamanship outside their experience, though they had swiftly become expert in others. They made up for the gaps in knowledge using their robust human qualities of common sense, utter determination, stamina and raw courage. When Serica was caught out in a ferocious levante off Gibraltar all this was heftily put to the test once again. After the first tremendous night-time squall George makes light of the physical effort needed to lower the jib, recover the tattered remains of the blown out mainsail and set the trysail during the storm, nor does he mention that, without about 24 hours’ worth of sustained work at the pump, Serica would very soon have sunk. Only inexperienced sailors would have chosen to sail into the Atlantic Ocean with decks that leaked like a sieve, not that they were aware of the extent of the problem when they set off from Lisbon. If George had managed to go slower and head down the seas, the deck would not have had green waves aboard, too many of which were finding their way below.

Serica’s classic lines gave her the enviable ability to sail to windward on her own, but this quality was not an advantage when the unattired George and Isabel went for a swim from their becalmed vessel a mile off the Spanish coast. As they enjoyed the cool sea suddenly, to their horror, the breeze came in firmly and Serica was off like a liberated stallion. A chase seemed quite hopeless, but thanks to Isabel’s resolution the runaway was eventually boarded, the alternatives being grim. This incident is the most memorable of the eventful cruise and it is much to the credit of George that he records such invidious occurrences with absolute accuracy, just like all the others.

George Millar’s accounts of his adventures are always like a box of jewels each giving dazzling pleasure and glorious entertainment, and never better than in this deservedly revived book.