Our first book had sold out a few years before, and we had the feeling it was time for a new edition in our now-standard robust softcover format, and that there remained an unplumbed audience among people who, though perhaps not habitual readers of sailing books, would appreciate the art, writing and social history contained within it. We suspected the Yorkshire writer, poet and broadcaster Ian McMillan was just such a person, and were delighted when he agreed to provide a new Foreword to Holmes of the Humber; here it is:

Our first book had sold out a few years before, and we had the feeling it was time for a new edition in our now-standard robust softcover format, and that there remained an unplumbed audience among people who, though perhaps not habitual readers of sailing books, would appreciate the art, writing and social history contained within it. We suspected the Yorkshire writer, poet and broadcaster Ian McMillan was just such a person, and were delighted when he agreed to provide a new Foreword to Holmes of the Humber; here it is:

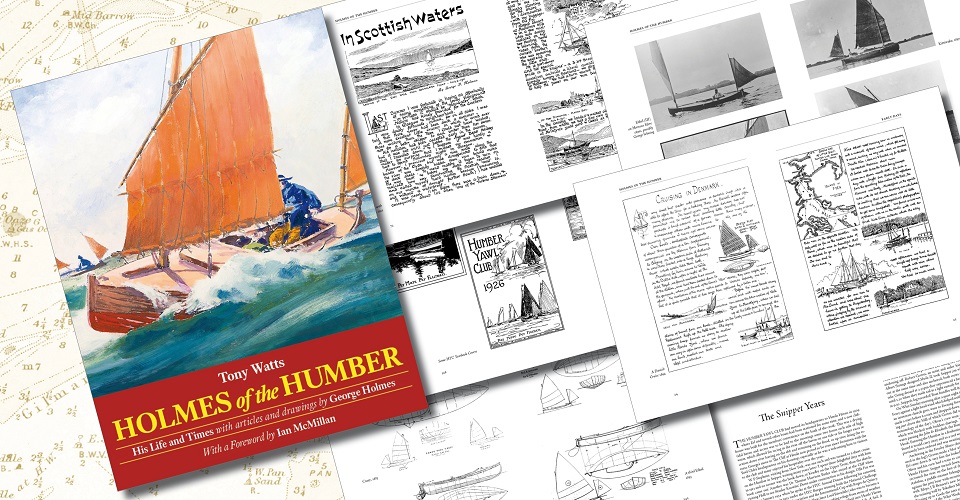

Words Written on Water

Welcome to a remarkable and many-layered book; to read it is like gazing into water that is apparently still but which, as you stare into it, begins to move. It swirls, it seems to deepen, it seems to contain stories that flit around like fish and somehow, in ways that you can’t fathom, it soaks you with tales and memories that you can never forget.

On one level this is the story of a man called George Holmes, who was born in 1861 and died in 1940. He was a businessman from Hull who was one of those people who grabbed every opportunity for learning and advancement that was on offer in those powerhouses of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He was a sailor. He was an artist. He was a writer. He was an inventor, developing the kind of boat known as the Canoe Yawl and he was a founder member of the Humber Yawl Club, which was based in Brough but had an influence that stretched across the world.

These are the facts, but this book is about much more than that single, if singular, life. Because of George Holmes and his questing intellect The Humber Yawl club became many things to many different people. It was a self-help group, an engine of industrial development, a haven for autodidacts and people who liked to discuss and argue and make points, and a place where ideas could be floated and tested to see if they would sink or swim. It reminded me of our little conservatory at home when I was a boy, where my dad, who was in the Royal Navy for two decades, would sit with his mate Jack Greensmith and tie fishing flies and mend things like clocks and frying pans and set the world to rights and compose letters to the Trout and Salmon magazine and talk about the open sea. They would have enjoyed the Humber Yawl Club and the club would have welcomed them with open arms as long as they had something to say and something to make.

I realise that I’m being a bit poetic here in my description of the goings on at the HYC and the towering figure of George Holmes but I make no apology for that. This is a poetic book written with love and skill; here’s the description of a first sight of Hornsea Mere: ‘Imagine gently rolling ground, richly and beautifully wooded, sloping up from the verge of a lake about a mile in length, and imagine this wood painted as English woods alone could be painted by the unresting hand of nature on a fine Autumnal day and you have Hornsea Mere as I saw it.’ This is English nature writing at its best, echoing people like Edward Thomas, the sentence sloping up as you read with the aid of the well-placed commas and words that fit exactly to the sense and the shape of the writing, like ‘unresting’.

Enjoy this book; enjoy the fact that places like Hull and the surrounding towns and villages have always been Cities (and towns and villages) of Culture, enjoy these vivid tales of vivid people, and gaze into the clear water of the prose, shining in the reflected sun that lights up the sky over the Humber.