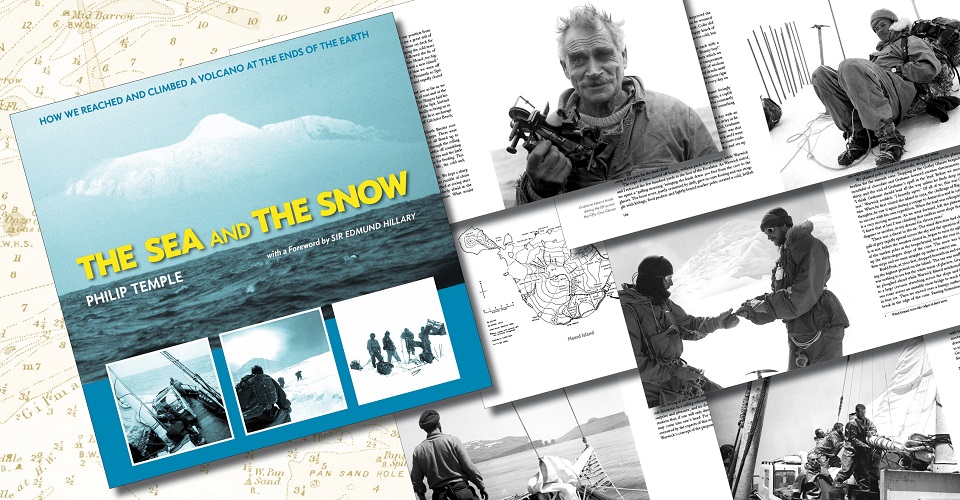

Philip Temple’s 1965 account of an outrageously bold expedition was published without fanfare, without many good photographs, and without even the benefit of a copy-editor; it vanished without trace. The Sea and The Snow came to our attention a few years ago as we prepared the books of H W Tilman for their new Collected Edition (he skippered the voyage described in Philip’s book), and we learned that a large collection of high quality photos from the expedition by its leader Warwick Deacock never, for some reason, made it into the original edition. Taken on his Rolleiflex 6 x 6 cm format camera, they lent themselves perfectly to full-page reproduction in the square format of our new edition of the book, on the basis if you have them flaunt them. From the perspective of his eighties, here are Philip’s thoughts on the Heard Island Expedition of 1964–5:

Philip Temple’s 1965 account of an outrageously bold expedition was published without fanfare, without many good photographs, and without even the benefit of a copy-editor; it vanished without trace. The Sea and The Snow came to our attention a few years ago as we prepared the books of H W Tilman for their new Collected Edition (he skippered the voyage described in Philip’s book), and we learned that a large collection of high quality photos from the expedition by its leader Warwick Deacock never, for some reason, made it into the original edition. Taken on his Rolleiflex 6 x 6 cm format camera, they lent themselves perfectly to full-page reproduction in the square format of our new edition of the book, on the basis if you have them flaunt them. From the perspective of his eighties, here are Philip’s thoughts on the Heard Island Expedition of 1964–5:

More than half a century on, it is easy to forget that no-one had done it before. There had been expeditions to Antarctica and the sub-Antarctic islands, but these had all comprised substantial bodies of men on ships of a sensible size fitted out for ice and the Southern Ocean. They may have had sails, but they were mostly powered by steam or diesel engines. Even when sail was the only option, back in James Cook’s day, his Resolution was 111 feet long and carried a complement of 112 men.

To most people in 1964, therefore, it seemed a preposterous proposal that ten men should undertake a sailing voyage of 10,000 miles across the Southern Ocean in a sixty-three-foot schooner to land on a harbourless, ice-covered island and make the first ascent of a 9000-ft volcano. Men in small ships had sailed to remote places before, alone or with small crews, but none with so much ambition.

But that was the point. As the expedition scientist, Grahame Budd, put it, its leader Warwick Deacock wished to demonstrate that, ‘If one will only dare, one can actually do the most unlikely things that may come into one’s head. For the hesitant, the diffident, and the many amateurs overawed by the experts of this world, this demonstration can’t be made too often’. Warwick’s vision captured the imagination of Sydney, from where the expedition began, and his energy drew enough support from its community, in finance and kind, to make it possible. That the expedition then succeeded in all its aims, exploratory and scientific, was a tribute not only to Warwick’s leadership but also to the skills and dedication of his chosen crew, under the sailing direction of that peerless explorer and skipper, H. W. ‘Bill’ Tilman.

It was a privilege to take part in the South Indian Ocean Expedition to Heard Island during that southern summer of 1964–65. It was one of the most important and memorable experiences of my young life. As, I think, it was for all of us, it helped shape who I was and went on to become. Ed Hillary wrote that what we undertook was indicative of our ‘courage and imagination’. If that was true, the example offered by such adventurous enterprises cannot be made too often, for the value it renders to its participants and for the encouragement it gives to others to also try the ‘most unlikely things’.