Blog suggests regularity – but we can’t promise you that. Here’s where we’ll put random book- and boat-related jottings as they occur. There’ll be a flurry of catching-up before we settle into some sort of routine.

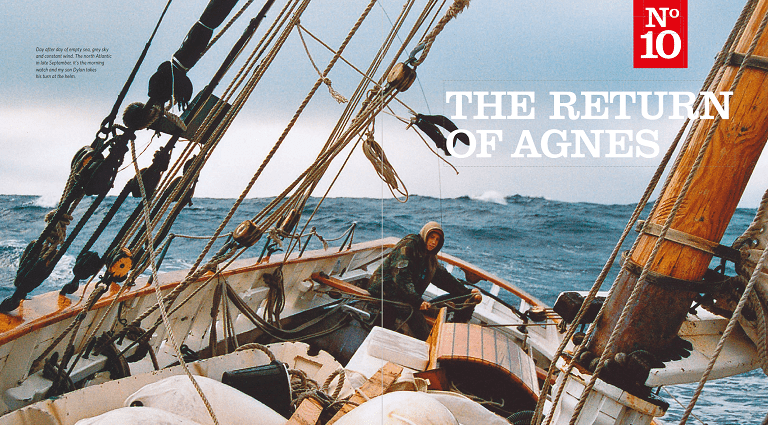

Working Sail – The Return of Agnes

by Dick | 15 Apr 2023

Luke Powell does not just build boats – he sails them too. Some years ago he rescued his then-largest build, Agnes, from the United States where she had fallen on hard times. Click the image to read an extract from his account of the voyage home to Cornwall, with a small crew including his fourteen-year-old son Dylan (pictured here at the helm).

Lodestar Boats: BUNNY in Finland

by Dick | 13 Mar 2023

Writing in 2003: Greatly facilitated (that is, made possible at all) by a rapidly made new mast from Essex boatbuilder Fabian Bush (see BUNNY in Morbihan), in July of this year Raid Finland followed the Great Glen and Morbihan Week in continuing to give me, Mike and Bunny a far greater breadth of experience than we might otherwise have had. Fourteen boats from throughout western Europe took part, and we gathered at the jumping-off point, Airisto in south-west Finland, over the two days before the start, allowing plenty of time for a gear check-out and shake-down sail, and to get acquainted with other craft and their crews. It’s a small world, and here I met again the Swedish family Palm with Suss, whom we last met in the Great Glen.

Read MoreAt Airisto we took over the Finnish Sea Safety Training Centre, where those of us not camping or sleeping on board were comfortably accommodated in the quarters normally used by visiting members of the merchant marine. To keep us fed Mike Hanyi, the Raid’s organiser, had retained a pair of chefs for the week. (Mike, confusingly, is an American of Hungarian/Austrian parentage, married to a Finn.) These initial accommodation and dining arrangements established the high standard to be experienced throughout the Raid.

Our initial briefing established the course for the first couple of days and explained racing and safety procedure. All boats would be subject to a gear inspection according to a checklist provided in advance; three motor boats would keep watch over the fleet, members of which could raise attention in an emergency or if requiring a tow, using a brightly coloured flag on a stick provided for the purpose. To the question ‘what about VHF?’ from one participant, I was unable to resist suggesting ‘wave the flag faster’. Combined with the eagle eyes of the motor boat crews, this system was to work very well. So on Saturday 26 July, in winds which were to be generally from the south and in record temperatures reaching over 33C (92F), the fleet set out on a (very) roughly circular course which would take it west into the Swedish-speaking Åland (pronounded auland, the au as in autumn) archipelago of some 6,500 islands, then eventually north, east, and south-east to finish at the charming town of Naantali, a few kilometres from the start, an overall distance of some 100 nautical miles.

The Baltic was a completely new experience; no tides for one thing, a welcome change after the washing machines, complete with spin cycles, of Morbihan. The elimination of tides as a factor in passage planning represents either a great bonus, or the removal of half the fun, depending on your point of view. The sea level can change by a foot or two over a period of days, but purely in response to air pressure or wind, and without, I believe, any discernible current. The water itself was unusual in being brackish rather than overtly salty – it had the smell and the taste of rivers and lakes, and caused us to float lower on our marks when swimming, which we did often, than in the sea off the UK. Navigating the archipelago proved not to be too taxing, although it could not always be assumed that the leading boat knew the way. It has to be said that one forested granite island much resembles another, however the main channels are indicated by an excellent system of purpose-built leading marks, and the more confusing areas are a veritable soup of clear alphabetical signs, which locate you immediately on the chart. One unavoidable fly in the ointment for serious racers: The area abounds in ferries, protocol and common sense dictating that we wait for them to complete their passage, which they make by pulling themselves along submerged cables.

For the most part we were in fairly sheltered waters, but with a couple of more open crossings which proved less boisterous than expected, one being subject to a slight swell from the south-west and with a good reaching breeze, and the other imposing a long-legged beat. We had bouts of quite heavy rain on a couple of days, but the brisk sail in warm sea, under a warm shower, and in a warm breeze took very little getting used to. Stopping for lunch generally involved beaching Bunny, or dropping a stern anchor and gently nosing into a a granite shore where we would secure to a tree or rock, sometimes to find some al fresco cooking well in hand.

As is no doubt common with these events, we would get a race-within-a-race as friendly rivalries developed between the more closely-matched craft. Mike and I were repeatedly confounded to see Penni, a beautiful Finnish Haven 12 1/2, skipper Seppo Narinen’s entire family of four on board, showing Bunny, only two up, a clean pair of heels. We fared better against Anna, an immaculately turned-out wooden Drascombe Lugger (with gaff rig) built by McNulty and Dutch owner Hans Manschot, mainly on account of windward ability. For our part, the substantially-built Bunny fared better the stronger the wind, as we were to experience a few days later, but in very light airs, and with what wind there was on the nose, we were able to compensate somewhat by sitting right down on the floor of the boat to reduce our windage, and nursing tiller and sheets to outpoint the competition. Interesting though such experiments are, we were pretty relaxed speed-wise – ‘All sailing boats are slow, some are just less slow than others ‘.

Der Griffioen was a well-preserved Belgian-owned Dutch scow dating from early in the last century, characterised by flat bottom, chine hull with pram bow, leeboards, short curved gaff, and matching curved jackstaff to which the Belgian flag was attached by the top only, being tensioned by a metal ‘boule’ suspended beneath. Speaking to her skipper Wouter van Roost (who recently completed Sail Caledonia 2003 within weeks of acquiring his boat) at the end of the Raid I cautiously mentioned what her shape put me in mind of. I needn’t have spared his feelings; from the start he had been regularly regaled by an ebullient French skipper, as the scow (not built exclusively for speed) was being overhauled, to the effect ‘Get that bloody coffin out of my way!’

Perhaps the epitome of the sail-and-oar ethic which inspires the Raid ‘movement’ was Kleiner Kerl, a charming varnished clinker double-ender of Norwegian design, sailed by German couple Stephan Rudolph and Angelika Runge. Her sprit rig, with split fore-triangle and topsail, made a magnificent sight on her length of around five metres, and provided plenty of strings to pull. With two rowing positions and a pretty slippery shape, her extremely fit crew had no hesitation in taking to the oars when the wind was less than favourable to her.

In addition to eating, and (moderate social) drinking well into the night, our time ashore was pleasantly punctuated with visits to a number of museums dedicated to the local culture, and in particular the boats which supported fishing and inter-island trading in past years, with their rugged demeanour and aroma of linseed oil and pine tar. Our imagination was captured by the somewhat Tolkien-esque ‘big boat’ (storbåt in Swedish), a beamy clinker craft of around 10-12m in length, gaff-rigged and open but for the enclosure of the rear few feet of the hull by a ‘clinker-like’ roof of longitudinal overlapping planks, the cabin entered by doors at its front. The owner and family would live in this space, the boat being used to carry cargo and livestock between the islands and nearby mainland of Finland, Sweden and even further afield. The stern-hung rudder on the steeply raked transom was controlled by a long tiller reaching right across the cabin roof. Ballast was rocks, although it has been suggested to me that sheep, with their natural aversion to water, are more effective if you have the room. We were to see a number of these craft afloat, both the well preserved and the recently constructed. Still on the cultural front, a visiting troubadour with guitar entertained us at one overnight stop, and at another we were captivated by an open-air recital by Tsakku, a well-known trio of three female folk singers, occasionally accompanying themselves with traditional instruments such as bone flute, drum and a form of lute.

Among a miscellany of other memories we took away: A flying door passing over our masthead one day proved to be a white-tailed, or sea, eagle. ‘It’s got no beak’ exclaimed Mike. ‘That’s not it’s head, it IS its beak’ I replied, eyeing the fearsome appendage. We saw another (or maybe the same one again) next day. At Lappo, our westernmost port of call, one of a yachtful of young Londoners tentatively approached Mike for local directions. ‘Sorry mate, I’m from Reading,’ was an answer he didn’t expect to get. Also on Lappo, another Raider visited the local blacksmith and purchased an ingenious iron clasp used for securing clothing. Uncertain of exactly how to operate it, he asked the craftsman to show him a second time, and was advised ‘Just look on my web site…’ Still on Lappo, we found ourselves at the epicentre of the Finnish/Swedish ‘knife culture’, according to the museum curator. Knife-oriented equivalents to Guns and Ammo magazine are popular reading in Finland, and Lappo’s past boasts a notorious couple of mass murderers, who despatched some scores of people in the 19th century, motivated only by a desire to have folk songs sung about them. Long winter evenings may have something to do with it.

The younger crew members hit it off together from the start, and the high point of their week was perhaps the midnight raid on Woge, a lake racer of advanced years and prodigious sail area expertly sailed by Manfred Jacob and his young son Marek, from Germany. Woge took line honours on every leg, and the conspirators resolved to slow her crew down a bit by relocating her (as they slept on board) some metres out in the small harbour which we occupied, and securing her between piles in such a way that release would necessitate a swim in the balmy waters; all of which was taken in very good part by her bemused occupants next morning.

The Raid was sponsored in part by a local oar manufacturer, Lahnakoski, who had generously provided each crew with new prototype oars they wanted thoroughly tested. These were, it appears, the world’s first machine-made, and therefore inexpensive, spoon-bladed wooden oars, the blades tipped with robust plastic to withstand the inevitable fending off to which they get subjected. Being made of pine they were lighter than our straight-bladed douglas fir oars, and we found them a pleasure to use. One day was declared for rowing only, and on the 3.8NM course Bunny, thanks in part to her slippery underwater shape, took the honours for boats having a single rowing position. Well, alright, Mike Hanyi in his lightweight Herreshoff cat ketch Coquina II beat us in, but was declared ineligible on a technicality – maybe because he had no crew aboard. In a remarkable feat of skill and endurance, Manfred sculled Woge the entire distance.

The Raid came to an end following a brisk sail close-hauled against a southerly into Naantali, where we gathered that evening at a dockside restaurant for the announcement of results, at which the award for overall winner to Kleiner Kerl was well received by all. The various trophies were ingeniously fashioned from oar blades made by our sponsor, with the exception of the overall award, an impressive wooden sculpture of a sailboat which may have given rise to an excess baggage charge had Stephan not been driving home. We made our farewells to those departing immediately, resolving to meet again on what is becoming the ‘Raid Circuit’ . Some crews then occupied themselves with boat recovery and departure, while half a dozen, Bunny‘s included, were to stay and take part next day in an annual local regatta. On this day Bunny came into her own; we were three-up this time, Johan, one of the Raid’s volunteer organisers, being our helmsman and tactician, I getting my 100kg where it was required outboard amidships and handling the mainsheet, and Mike taking care of the jib. Thus manned, and with every nonessential item removed from the boat, we romped around the 5NM course unreefed and reasonably upright in winds gusting to force 6. The potential for a ducking was as strong to windward as to leeward, as the sudden disappearance of the wind would occasion a frantic scramble inboard. One or two raiders of lower freeboard and tender nature wisely retired, and I believe there was one dismasting and a flooding among the traditional craft, who were sailing their own ‘star’ course within easier reach of assistance. Woge beat everyone in of course, but was occasionally recognised from afar with her mast all-but-parallel with the water surface.

On the logistical front, I chose to ship Bunny from England to Turku (very near the Raid launching point) with Mann Lines from Harwich, Mike and I flying out later to join her. In this we honoured the practice of the Victorians Strange, Holmes and others in shipping their boats to their Baltic cruising grounds. I called Manns some months beforehand to secure Bunny‘s berth on board the weekly sailing, but was told ‘Just call us the week before you want her shipped, we’ll fit her in’. I took the precaution of deploying fenders all round as well as the boat cover, and her passage proved trouble free in both directions. I had been worried in advance about arranging tows in Finland, but Mike Hanyi assured me that ‘your boat going swimming will not be a problem’. The considerable saving in car ferry cost and time off work proved worthwhile, and in the event we were able to secure tows to and from the launch and recovery sites from other participants for the bargain price of a dinner and the cost of the fuel.

Raid Finland may, by comparison to the Great Glen Raid and Morbihan Week, be a modest affair, but this in no way impaired the quality of organisation both ashore and afloat, nor the safety arrangements. Mike Hanyi, his wife Susa, and the team of volunteer helpers worked hard over the preceding months to ensure a repeat of their first year’s success. As an indication of ‘customer satisfaction’, a number of this year’s participants were veterans of 2002, a trend which is very likely to continue. I have recently heard that the event is next year to be supported with a European Union grant, it having been a labour of love for the organisers so far.

Bunny has proved to be a dry, forgiving and well-performing boat, never failing to delight her crew and impress onlookers. But just two years in, I am by no means free of my indentures; my boat handling ability does not yet do her justice, particularly as regards getting under way and bringing up in a variety of conditions, but perhaps that is to be expected at this stage. I confess that my systematic investigation of the handling characteristics of the yawl rig, as described in the second Albert Strange Association book by Jamie Clay and Mark Miller, is long overdue. On the plus side, our participation in organised events has gained Mike and me more experience and confidence than we would have achieved alone. In addition, it may be noticed that our most recent outing was entirely free of the self-inflicted problems encountered in the previous two. This is not a statistically significant result, but I feel things are improving. For the immediate future I plan to cruise home waters in 2004, exploring the Thames and Medway estuaries. Looking further ahead, my sights are already set on a slightly larger vessel: she will be ballasted and with a small cabin, engineless, still (occasionally) trailable, and transportable one way or another to anywhere I would want to sail her; she will be long in the gestation, and by the time the project bears fruit I hope my abilities will be some kind of match for her.

Bunny is a canoe yawl – there’s lots about them in Holmes of the Humber

Working Sail – a foretaste

by Dick | 7 Mar 2023

Working Sail has gone to press. We’ll tease you with a few snippets from Luke Powell’s reissued book between now and its publication on 18 May. Today, you might like to read its pair of Forewords, by Tom Cunliffe and Jeremy Irons, both afficionados of the kind of sailing which has been the focus of Luke’s career, and doing a good job of conveying its sensations and atmosphere. Click the image to download them in PDF form. You can order the book here.

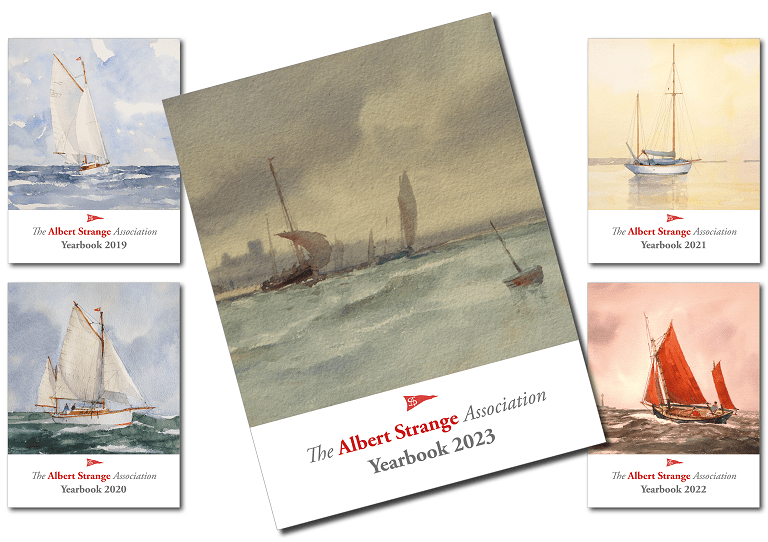

You would likely like* The Albert Strange Association

by Dick | 21 Feb 2023

An annual pro bono job here is to lay out the ASA Yearbook, now in the fifth iteration of its swanky format in full colour (except where some of the photos are knocking on a bit); the 2023 Yearbook has just gone to press. Here’s what you’re missing by not stumping up a mere £15 annually. The ASA exists to preserve the world’s memory of Albert Strange, and also to foster interest in traditional boats, their building and sailing. It sends out a monthly email Newsletter which is always an entertaining and informative read. Many of us (a relative term – it won’t be a stampede) will be at this year’s Annual General Meeting at Bangor, North Wales, on the second weekend in March. Might see you there? You can turn up and join on the day! More information on the ASA website.

* Anyone recall Dr. Strangely Strange? No relation AFAIK

Lodestar Boats: BUNNY in Morbihan

by Dick | 13 Feb 2023

In May of this year [I wrote in 2003], following a small refit and a hull repaint occasioned by the Loch Ness beaching, Mike and I were back again at this superb cruising ground with Bunny to participate in a week-long rally involving some 800 boats from tall ships down to cockleshells, most with some claim or pretension to tradition. To attempt a catalogue would be impossible and unnecessary – you name it, it was there; however the local ‘sinagot’ fishing boats, alarmingly lofty luggers with up to three masts, each carrying a passing imitation of a Roman imperial banner, are worth singling out. The fleet was divided into seven flotillas according to size and type, each starting out from a different one of the many small ports in the gulf, and spending each night at another, so criss-crossing the entire body of water. At each stop we would find entertainment in the form of local bands and singers, with freshly-prepared seafood on shore or at a variety of restaurants. Mike and I were camping at a fairly central location near Port Blanc, and ferried between boat and camp at the ends of each day by a special bus service. Throughout the week order was to be maintained by a large fleet of RIBs manned, unnecessarily as it turned out, by the CRS – the French riot police.

Read MoreWe were left to our own devices for the first few days and seemed to have the entire gulf to ourselves, but for bumping into sailing photographer and writer Kathy Mansfield, a near neighbour of ours and a fellow Henley Whaler, out on the water. This secured us that hard-to-achieve thing – a view of ourselves under sail, and obviated the need for the out-of-body experience which we came close to a day or two later. The organised sailing began mid-week. Although the event was ostensibly a series of races, the start and finish procedures were relaxed to the point of non-existence, and the liberal use of motors, and even shortcuts to the planned course, by our competitors slightly surprised Bunny‘s straight-batting crew.

The week was cloudless but for the last day, and the winds could have exceeded force 3 more often than they did; but the event was not without incident, particularly on account of the tide races from which this time there was no escape. In fact on the day of our arrival and launching at Larmor Baden I had forgotten to set my watch to French time; as a direct result I found myself rowing us flat out, but getting nowhere over the ground, as we attempted to pass through the narrows at Port Blanc against the by now considerable ebb, watched with polite interest by onlookers within chatting distance on shore. We were rescued from this embarassment by a tow from a local fisherman.

The tide came into play again a few days later as, along with a large percentage of the entire fleet, some hundreds of boats in all, we poured through the narrows known (by the English anyway) as the Gut, approaching the neck of the Gulf. With virtually no wind we had no steerage way, and with hindsight should have been rowing hard rather than using the paddles to little effect, other than to point us more or less where were were going. This probably contributed to a nasty incident when we, and another small boat bearing a very young family, were struck from behind by a briskly-moving and heavily built gaff ketch of some 60-70 feet; it was motorsailing to maintain some sort of control, but a bit faster through the water than was strictly necessary, I thought. Fortunately no damage was done to either of the boats or their crews, but the tiny girl in the bow of the other small boat will never forget the black gaffer’s stem towering over her and shoving her boat aside. Knowing what I now do of the tidal conditions at Morbihan I might have been tempted to take along our outboard motor, which would mount on the starboard quarter. But with hindsight, and the experience now gained, I am glad it remains, brand new and never used by the previous owner or myself, in my garage. Long may this continue – I suppose I should really sell it to remove temptation altogether.

Sailing downstream from the impossibly picturesque port of St Goustan a day or two later we succeeded in running aground in thick mud on a falling tide. Having failed to reach a passing CRS boat by throwing our tow line, I was instructed by its skipper to walk the line to him before we were completely high and dry; I had descended thigh-deep in mud and still not found my footing before I decided against it. We spent a very hot couple of hours in the shade of Bunny‘s scandalised main waiting to float off, and noticed the surprisingly long trail cut in the mud by our centreboard before we had even realised anything was up. As we finally floated off the CRS returned and offered us a tow, without which we would not have made the next stop, on the other side of the Gulf entrance, in time for the afternoon leg. This was accompanied by the earnest assurance that they were responsible for our safety so could not leave us unattended to regain our flotilla alone, a somewhat hollow statement as we would soon find out. The tow went well, and at considerable speed (a canoe yawl can indeed plane) until at the confluence of the arms of the Gulf it became clear that our guardians had no no idea where we were headed; once satisfied that we at least knew, they cast us off there and then to finish our journey alone. About this we felt comfortable, if slightly exposed to the fetch from the Atlantic on our starboard side, until almost immediately a strong gust carried us onto submerged rocks a few yards to port. Our centreboard had just made contact with them when another CRS boat came along, to which I quickly hurled our tow line, and a nasty incident was averted.

The highlight of the final Saturday was to be the Grand Parade of the entire fleet of 800-plus boats on the open Atlantic outside the gulf. With unregistered local boats turning out, 2,000 craft were expected, as in 2001. However a certain relaxation on the part of the bus company put paid to this as far as Bunny was concerned, as we arrived at the boat too late to keep the rigid timetable. Instead we sailed clockwise around the gulf from St Armel to Port Blanc to haul out, intending to watch the entire fleet sailing back on the flood through the adjacent narrows. As we approached the narrows ourselves at slack tide, suddenly windless and with virtually no steerage way, I noticed a large speed boat barrelling towards us. It soon became clear, too late to deploy the oars, that her skipper was too busy talking to his girlfriend to notice our yawl dead in the water ahead of him, broadside on and with all sail set. After some frantic seconds waving and yelling at the tops of our voices we were all set to jump for it when he looked up, noticed us, and steered around us with just yards to spare, a broad grin on his face.

Having picked up a buoy at Port Blanc, and fed and watered at the restaurant overlooking the moorings, we strolled along to the wall by the narrows to watch the procession of the major part of the fleet up towards the head of the gulf. Still virtually without wind, but this time on the strong flood tide, hundreds of boats of every size, description and indeed orientation were spat through the gap in a spectacle which lasted an hour or more. Once again the larger craft were obliged to motor to maintain control, and this resulted in at least one small unpowered vessel becoming hemmed inside the wake of one and before the bow wave of another. Her crew had no option but to row like mad to keep station, until the CRS noticed their plight, and rammed them unceremoniously out of harm’s way with their RIB. The entire show took place to the continuous sound of the tiderace and its satellite eddies, like that of a waterfall.

We recovered Bunny onto her trailer and, mindful of the pressure of numbers on the slipway, I decided to tow her slowly the couple of hundred yards to the car park before unrigging her. As we ascended the gentle slope I could hear a car horn and some verbal altercation behind me and, this being France, thought nothing of it. I was rewarded for this lapse with summary dismasting by an overhanging tree; a final hard-won lesson to be taken home. On the upside, the mast now stowed entirely inside the boat.

As we settled down to doze in the lounge aboard the ferry taking us back to Portsmouth the last image we beheld, in a large colour photograph on the wall before us, was of the very same gaffer which had nearly been our nemesis a few days before.

Bunny is a canoe yawl – there’s lots about them in TheCanoeYawl and Holmes of the Humber

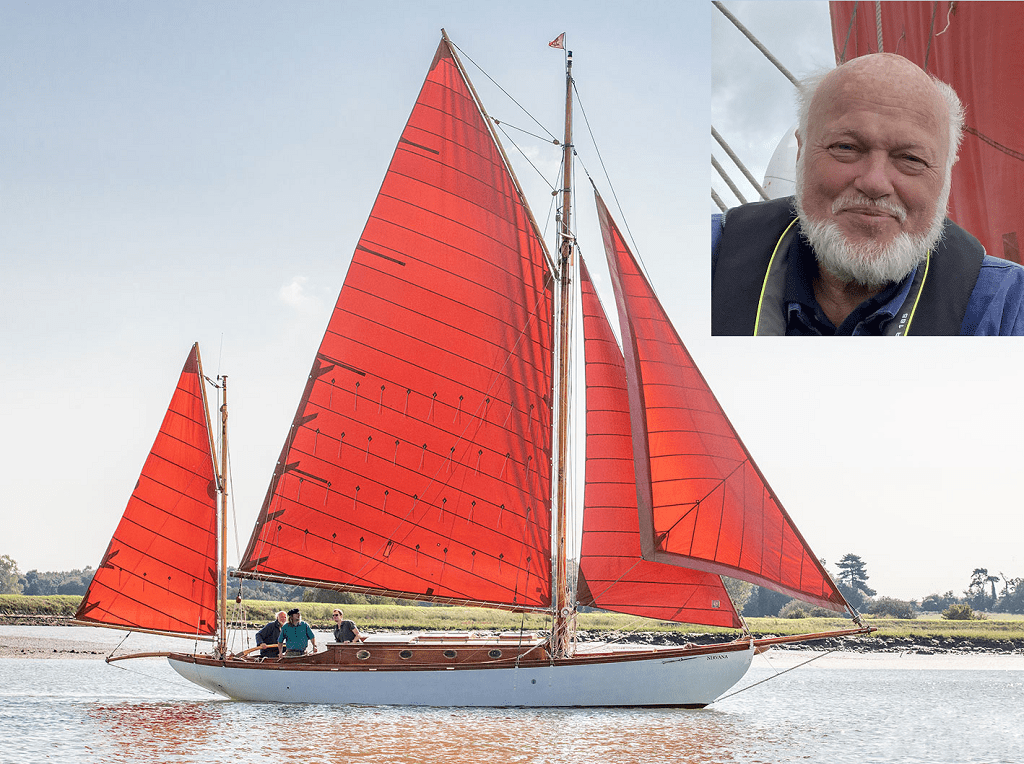

A Stranger takes his leave

by Dick | 8 Feb 2023

As some of you know I have a soft spot for the designs, the writings, the voyages, and the art of Albert Strange (1855–1917) and so do enough others to function as The Albert Strange Association, formed in 1978. The largest concentration of AS boats is on the English East Coast, and the flagship of the fleet is the magnificently restored thirty-six-foot Nirvana, in the care of Pete Clay for many years. We Strange skippers try to get together on and off the water a couple of times each year. Some of us will meet tomorrow, with his large extended family and many friends, at the funeral of Pete, whose failing health got the better of him recently. But we’ll repair afterwards to a celebratory gathering, to remember a kind, charming, wise, knowledgeable, and quietly (often wickedly) funny friend who we’ll sorely miss.

The ultimate Cooke booke

by Dick | 31 Jan 2023

Bear with me, this is going somewhere relevant to us. Many years ago I first entered the book trade, as an assistant at Foyle’s bookshop in London when it occupied its ancient premises at the top of Charing Cross Road, not the swanky place just down the road it has today. Some readers may recall its idiosyncrasies; for example to buy a book you handed it to me, I gave you a ‘chitty’ to pass, with your payment, through the bars of an enclosed cash desk some yards away, you brought back the receipt and I let you have the book. One wag of a customer said, when I sent him off to the cashier, ‘that’s somewhere down the Strand isn’t it?’

Read MoreAfter a few months a publisher’s trade rep came in and asked me ‘can you drive?’ There followed two years on the road for the hallowed firm of Ward Lock before I tumbled out of books and eventually into computers, to return, as Lodestar Books, years later. Anyway, in those glorious days before the internet and streaming services books had a much larger claim on our attention than they enjoy today. Cookery was the best-selling non-fiction subject, to be superseded later, and briefly, by computing. Mrs Beeton was Ward Lock’s prime cookery book property, her monumental Cookery and Household Management being sliced and diced into numerous smaller volumes with titles like Everyday Cookery, Family Cookery, Weekend Cookery and what-not.

Enter Francis B Cooke (1873–1974) who took a leaf from Mrs Beeton’s book in his series of practical sailing titles from 1903 to the 1950s: Cruising Hints (6 editions), Seamanship for Yachtsmen, Single-handed Cruising, Yachting with Economy, Weekend Sailing… you get the idea. It was high time someone condensed his output into a single non-redundant volume, and I took on this task around 2011. This involved obtaining every edition of all his books, about 25 volumes in all, scanning their 5,000 pages of text, digitally cleaning up hundreds of pen drawings, and condensing and re-setting it all into the 700-odd pages of Cruising Hints, Seventh Edition, which appeared in 2012. In those days I printed digitally, 100 copies at a time, and sold only direct to the reader, there being no room in the costings for trade margins. We sold three or four hundred copies, including a later paperback of slightly reduced format.

Cooke remains an invaluable reference to British yacht designs of the first half of the twentieth century, and Cruising Hints, 7th Ed., contains all of his design commentaries, with drawings, and much else besides in the way of his writings on technique and his cruising yarns. Good bunkside fare, I like to think. Little has changed in the world of trad sailing from his day to ours; well, radio and GPS I suppose. As Sam Llewellyn, publisher of The Marine Quarterly, said: ‘…much of practical value, and plenty to disagree with’. Now out of print, it’s recently available as a PDF with all sorts of tricksy hot-links between the contents, design list and index, and the design commentaries and drawings. And you don’t need to rotate the book to view the drawings.

Lodestar Boats: BUNNY in the Great Glen

by Dick | 31 Jan 2023

I wrote in 2003: The Great Glen Raid was, for the three years 2000-2002, a rally for sail and oar craft from Fort William on Scotland’s north-west coast to to Inverness on the east, through the Caledonian Canal, most of which consists of lochs, as opposed to locks. The term ‘Raid’ was coined by its organisers, a non-profit French body called Albacore, as shorthand for an independent sail-and-oar expedition. The same event continues today with different management, under the name Sail Caledonia.

Read MoreOn making enquiries about the 2002 Raid via the local Enterprise Board (one of its sponsors) I found myself in contact with Bill Sylvester, the board’s chief executive and a then boatless sailor with dinghy racing experience; this was an opportunity too good for this crewless skipper to miss, my son Mike being unavailable, so Bill and I made it a date for late May.

The north-easterly route through the Great Glen can be, and indeed was to prove, demanding and exposed. Wind is generally on the nose or tail, any strength in it presenting the discomfort of beating or the risk of broaching in the considerable waves which can develop, especially on Loch Ness. In fact there were seven capsizes, but on the smaller Loch Lochy, the previous year. Bunny was the smallest boat there by a good couple of feet, her acceptance being in doubt until the organisers were satisfied by her sturdy lines, ample freeboard and decking, and internal lead ballast, and persuaded of the (combined!) experience of her crew. By this time, mindful of the running repair found necessary at Morbihan, I had endeavoured to replace every worn or potentially troublesome fitting or piece of cordage on her.

The fleet was craned into the water at Corpach, just in from the western end of the canal. As we made ready afloat a nearby skipper asked me of Bunny ‘Is that a Victorian gentleman’s canoe yawl?’ I should have had the presence of mind to respond ‘No, on the first two counts’, but I never think of these things until afterwards. That skipper turned out to be George Trevelyan, who has campaigned his ageing Montagu Whaler Collingwood, with crew of up to a dozen or so, across Europe. She was the previous year’s Raid winner and, at 27 feet, this year’s largest competitor. George lives a few miles from me, near Henley, and there each Wednesday night I am now one of his galley slaves as we exercise Collingwood‘s successor, a modern replica New Bedford whaler, Molly, on the Thames. This takes place all year round, in conditions ranging from balmy to Shackletonian, the later compensation being an earnest review of technique at the Anchor pub.

The fleet of thirty or so Raiders spanned a broad spectrum including a Hebridean Sgoth and an Orkney Yole (both substantial clinker double-enders); Ian Oughtred’s Jeannie II, a Norwegian-inspired clinker ply double-ender, still under construction on her arrival; some GRP Drascombes; Ofelia, a beautiful Swedish incarnation of an old Hartlepool pilot boat design; another Swedish family boat Suss, resembling a large cold-moulded Merlin Rocket; two luggers from King Alfred’s School in London, designed by Nigel Irens and notable for their ability to field any number of masts to taste; and one or two ‘development’ types in both high- and low-tech materials.

Day One involved a figure-of-eight leg ‘at sea’ in waters off Fort William, the aim being to verify the seaworthiness of boats and crews. There was hardly any wind, but we got Bunny round without resorting to the oars. Day Two began with the ascent of ‘Neptune’s Staircase’, a flight of eight locks, followed by a timed canal row by the skipper for six miles (his crew claiming tennis elbow). Bunny is easily rowed but presents the problem of what to do with the helmsman, the tiller obstructing the central location he needs to take to balance the boat. Bill had either to stand astride the tiller, or unship it and sit on the aft deck, steering crudely with cord tied to the rudder head. I think the answer, not yet implemented, is a detachable perch on the aft deck bridging the sweep of the tiller.

There followed a fast run down Loch Lochy of about ten miles, in force 4-5. Fortunately, only the day before the Raid began Bill and I had made a pole for the jib at his home in Inverness. A preventer would have been handy, but we made do with a crew member holding out the boom. Despite carrying three on this leg, we got a palpable surge of speed on each overtaking wave as it got beneath Bunny‘s ample (perhaps ‘powerful’) hindquarters. The 20-foot Ofelia recorded a maximum six knots or so over the ground (here more or less synonymous with ‘through the water’) on her GPS, and we were keeping pace with her. On a run there was little to choose between the disparate fleet of boats, and this made for quite a protracted social occasion. Our third crew was a journalist from Sailing Today, which was to give the Raid good coverage, and Bunny a full-page photo.

Day Three on Loch Oich, only about four miles long, gave us our best finishing position. Winds were light and variable. After a spot-on racing start we held second position (behind a far larger boat) right up to the last 50 yards, when we were just pipped by the stealthy Ian Oughtred and another boat, to come in fourth. We dropped the main before sailing into a pontoon berth under jib and mizzen, under full control naturally, to be pleasingly complimented on so doing. We were next to Ofelia, whose Swedish skipper declared he loved every part of Bunny except THAT! – pointing to the tip of her bowsprit. Here, in recognition of my dubious close-quarters handling, and the ruggedness of the galvanised cranse iron, I had appended a fluorescent yellow soft plastic ball to both warn and protect other craft. This was soon to go in a collision (fortunately one where Bunny played a passive role), to be recovered from the water by another boat and giving me cause, for the first time in many years, to ask for my ball back.

Day Four was the first on Loch Ness, at 22 miles by two or so and very deep, the largest single volume of fresh water in the UK, and virtually sterile, disappointingly for monster hunters. Force 4-5 on the nose, and we beat into it under full sail for all we were worth, Bill’s inclinations having overcome mine as regards reefing. I believe, in fact I’m sure, we would have made better progress to windward with a reef in the main and with the boat, and particularly the centreboard, more upright. Unfortunately I was soon without a tiller extension as the ring on the clevis pin attaching it to the tiller head snagged on my clothing and pulled out the pin itself, which disappeared somewhere in the boat; this left me unable to get my 16 stones (220lbs / 100kg) right out where it was needed. As a result we were ‘lee rail under’ for about four solid hours, during which time we passed five boats, larger than us (as they all were), and all of which subsequently were obliged to turn back or accept a tow.

To be fair, we too would have taken a tow soon; even at our fair lick the leg was to take us a month of Sundays. The decision was forced on us when I finally bungled a tack, accidentally jamming the mainsheet full in on the turn, and instantly capsized us in a by now force 5 wind. I groped around underwater to free the mainsheet, then we set about righting Bunny. Bill took to the centreboard, and I made to roll in as she came up. As she did so, however, the stern 425lb buoyancy bag, secured only by tapes through loops on its seams, quickly squeezed out through an improbably-small gap and bobbed away down the loch, in a scene strongly reminiscent of the 60s TV series The Prisoner. Bunny sank rapidly beneath me by the stern, a disconcerting sensation, the bow bags arresting her descent with just a foot or two of her stem out of the water. Although we were not far from shore, the bottom falls away steeply to about 800ft, so this was a very disturbing development. Bill and I felt in no serious danger in our automatic lifejackets, given the proximity of the shore and the arrival of the safety boat before too long; however the incident did call into question, in my mind at least, the practicality of an automatic inflatable jacket in situations where some personal manoeuvrability is needed in recovering a capsized boat. I felt distinctly hampered by mine, which imposed the typical reclining orientation on me, by comparison with, for example, a buoyancy aid having foam filling front and rear. This feeling was not mollified by my reading more recently that lifejackets of this type, by holding the wearer’s face to wind and sea, have been implicated in a number of drownings in conditions somewhat rougher than ours on the day. A moot point, anyway.

Bunny was dragged to a rocky shore by the safety boat to be bailed out before, aboard the organisers’ motor cruiser, we changed into the dry clothes we carried in waterproof drums on board, and towed her unmanned to the next scheduled stop as we recovered our circulation. Incredibly, there were no losses from the boat (the buoyancy bag and a wandering floorboard having been retrieved by the safety RIB) nor any damage except to paint and pride, but a swim in Loch Ness, even in June, is not so warm as you might think. We were very glad at the end of that day of our berths aboard Fingal, a 100ft-plus converted trading barge, complete with hot showers, laundry, drying room and food cooked for us. Today Bunny‘s stern buoyancy bag is secured by a comprehensive lacework of webbing, the load shared between a dozen or so substantial eyescrews. As for the mainsheet, in fresh conditions it is now re-routed at the exit from its block so as to be unjammable, whether by intent or by accident.

Day Five (the second half of Loch Ness) presented a more gentle beat. The wood screws securing the bumkin bracket were found to have pulled out of an aft deck beam, perhaps as a result of the beaching and manhandling the day before. This gave us a surprisingly lacklustre performance under main & jib only. Eventually I found I could lash an oar along the quarter and tie the bumkin down to that. Once this was achieved we quickly passed five other boats, demonstrating the power contributed on the wind by the mizzen, despite it being slightly blanketed on this point by the helmsman. After the finish line we had a further beat down the wide canal, passing another four or five boats doing the same.

These two days had been my first lengthy experience close-hauled with Bunny. On this point of sailing Bill and I noticed a couple of things about her: Firstly, the mainsheet alone, running from the block on the centreboard case to a point two-thirds of the way from the mast along the boom, was incapable of getting the boom inboard enough; it was necessary for the crew to manually haul the boom in whilst the helmsman took up the slack in the sheet. The only alternative I can imagine is a mainsheet horse bridging the tiller aft, but the magnitude of the problem hardly merits this measure. Secondly, the middle third of the main, vertically speaking, for a couple of feet behind the mast, was distinctly backed by the jib, about which we found we could do nothing at all; for example adjusting the jib sheet travellers did not help. This seems to be inherent in the gunter sail plan; whether other 3/4-rigged craft experience it I don’t know. A mashtead rig would get the effect, if at all, at the top of the main where it would matter less. Perhaps we should have eased the sheet a bit and pointed lower.

Day Six had us rowing, manhauling and locking through a few miles of canal. Day Seven, the last, was my 50th birthday; if this turns out to be ‘mid-life’ I have a long sailing career ahead of me. We raced on the Moray Firth in force 4-5, a cautious downwind leg followed by a beat back. The bumkin bracket was by now temporarily fixed with a roofing bolt. We had the main reefed for the first time as we didn’t know quite what to expect out there. In strong winds it can be tricky to reef a gunter sail, since you have to drop the yard in order to reposition the halyard on it. I think it might be possible to design a solution involving an extra masthead sheave and a bit more cordage. It proved a boisterous sail, one of the King Alfred luggers capsizing, and Collingwood under her huge white lugsail, complete with George on the trapeze, hands laced behind his head in supreme insouciance, was a sight to behold. Bunny shipped only spray despite being driven very hard.

At the final reckoning Bunny was placed seventh in her class of 18 boats up to 22ft or so in length; she had attracted admiring comments throughout the week for her design, build quality and general turnout. The satisfaction of this novice in completing the Raid and confirming Bunny‘s seaworthiness was a warm feeling indeed.

Bunny is a canoe yawl – there’s lots about them in TheCanoeYawl and Holmes of the Humber

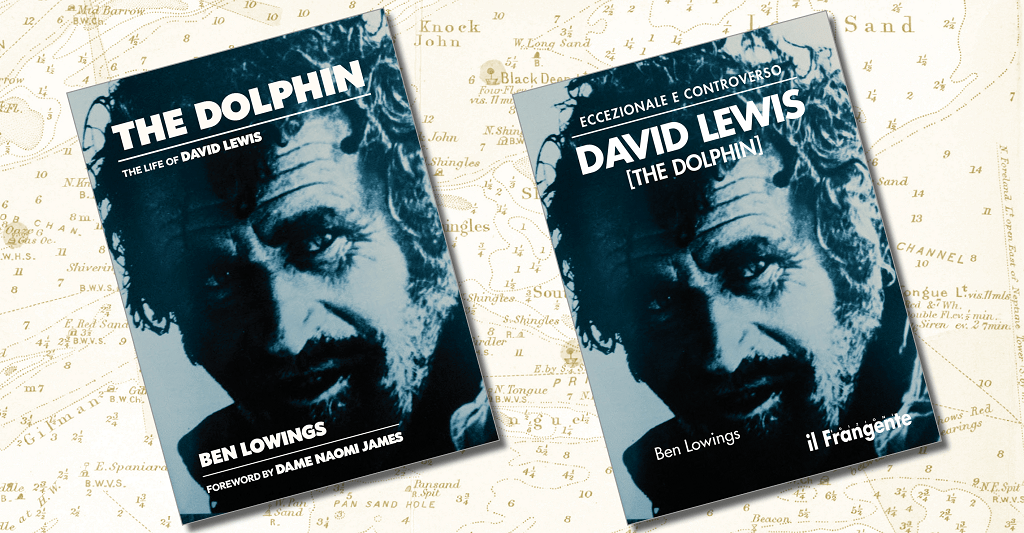

The Dolphin – Italian edition

by Dick | 29 Jan 2023

Lodestar Boats: BUNNY

by Dick | 28 Jan 2023

Readers might wonder whether this nautical publisher has any sailing experience himself; well, yes, though I seem to spend far more time messing about with boats then messing about in them. Here and in later posts I record my dubious credentials.

Read MoreI wrote in 2003: The mid-life crisis is a luxury peculiar to the western male with too much time on his hands or, perhaps, one who is oblivious to the demands upon it. In my case, after too many years aspiring to be a sailor and doing nothing about it, I finally acted with some RYA training courses and occasional crewing on a yacht, and the acquisition of a 15’6″ David Moss Sea Otter canoe yawl, now named Bunny (my grandmother’s nickname), in 2001.

My attraction to the canoe yawl was based solely on written accounts rather than experience, of which I had none, but it has been well rewarded by the adventures, and contact with like-minded people, into which Bunny has led us. Here’s how I got started.

First steps

I contacted David Moss in early 2001 to learn about the 3/4-decked canoe yawls he has been creating at his yard near Fleetwood in Lancashire over the last 15 years or so. David was booked up as regards new building, but he soon tipped me off that a used 15-footer, in fact the only one then in existence (his other open examples being 13 feet) was just coming onto the market locally to him, and he assured me that on seeing her I would buy her. He was right. Canoe yawls from any stable don’t come on the market every day, and this one was superbly well-built and in a pristine condition which belied her 12 years. Behind her gleaming recent paint job lay strip-planked douglas fir and a diagonal hardwood outer skin to a total thickness of around 5/8″. Her fit-out had cockpit coaming, side-benches, removable thwarts, and the rowing seat on the centreboard case all in varnished iroko, surmounting a flat floor of removal panels painted with the same businesslike non-slip as the deck. The sitting-out perches added to the side decks by her owner were a nice touch. Her rig was gunter main and mizzen, with a furling jib, and tan sails bearing the unusual label ‘The Fleetwood Trawlers Supply Company’ – a connection with David’s earlier years building or repairing the local working craft which fished from Morecambe Bay to the Arctic, and from Newfoundland to Russia. Hardwood cleats, tufnol blocks and galvanised metalwork completed her unpretentious appearance.

I had called in on David on my way to see Bunny for the first time, when he showed me the half-model from which he took her lines, and the temporary mould on which he built her in 1989, now re-erected as he was to construct a second of this size, to be lug-rigged and with a bit more sheer to her. David’s yawls are inspired by the Victorian craft of Holmes and Strange but, quoting him from Water Craft, May/June 1998: ‘With this design I started to develop my own version of the canoe stern which is very buoyant in the quarters but hollow on the waterline. The bow has ample fullness to balance the hull and the beam is carried aft of centre. Although this stern is difficult to build, even using strip planking, it proves its worth when sailing, making a very fast and able boat even in a choppy sea, almost planing in the right conditions.’ A visit to David’s yard is always a great pleasure, but be sure to allow an hour, preferably two, to gain full benefit from his passion for his craft and enthusiasm for communicating it. On my second trip, with my son Mike, to collect the boat I dropped by again, and received an excellent impromptu lecture on the marinization of a Yanmar truck refrigerator motor, illustrated in pencil on the primed hull of the 25-foot yawl then building.

Mike and I trailed the boat home and for the remainder of that year kept her at a local flooded gravel pit, the attractions of which we soon exhausted. It was here that an embarassing launching accident occurred involving a steep ramp, an unwittingly cocked jockey wheel, and a nearby pontoon, splitting the beautiful laminated tiller which encircled Bunny‘s mizzen mast; the situation was not improved by my attempt at repair. Over the following winter David created a substantial and even more beautiful replacement in iroko and ash, complete with his trademark otter’s head hand grip. These days I am cautious about exactly when in the launching process I hang the rudder.

Going ‘foreign’

For a couple of years my work took me to Paris, returning home to the UK each weekend. In early 2002 I had what seemed the adventurous idea of keeping Bunny somewhere in France, and settled on the Gulf of Morbihan, a large, sheltered natural harbour, full of islands, in southern Brittany. So in the February I trailed her there, and ‘moored’ her ashore at the tiny port of Arradon. As things turned out Mike and I only managed to get in a couple of long weekends, travelling down from Paris on the TGV, once as early as March, yet in T-shirt weather. Fearful of the notorious local tides, with a range of up to 16 feet and running at up to 9 knots, we kept well away from the narrow mouth of the gulf, but did manage to circumnavigate the large Isle aux Moines (Monks’ Island), not a bad effort for a couple of beginners fresh off the local gravel pit, we thought. Halfway round, the clew outhaul on the mizzen broke; we picked up a nearby vacant mooring and while Mike balanced the boat I was able to stand on the aft deck and reach up to repair it. Until we gained confidence with Bunny‘s ample sail area we would frequently reef the main or drop it altogether, sailing

perfectly balanced under jib and mizzen in anything like a breeze. At this early stage in our careers we found the ‘air rudder’ capability of the mizzen very handy, particularly when getting under way in a crowded anchorage; however you don’t get much purchase trying to shift the boom by its inboard end against the wind. I have a pet theory that a sliding or hinged ’tiller’ on the boom would increase leverage and make the technique more effective.

Towards the end of one afternoon, after a rainy day spent ashore, the sky brightened up. We stirred ourselves from watching the world go by at the head of the harbour creek in Vannes and dashed down to Arradon in our hire car to get in a couple of hours or so on the water. Dropping our mooring we ran in blissful ignorance down the gulf to return, and repent, upwind at some leisure, with darkness rapidly falling. We novices were too easily seduced by the marked reduction in apparent wind when running. Reading the chart by moonlight proved quite difficult (since many of its colours appeared the same uniform grey) as we beat through the confusing rocks and islets on the approach to Arradon, until at one point Mike said ‘Sshh – what’s that noise?’ Recognising it instinctively as water lapping gently over rocks a few yards ahead, I went about very sharply, having mistaken a small headland for an island in the darkness, and gone ‘inside’ it. A few gybes later (some of them intentional) this new intelligence quickly got us our correct bearings and we returned to port undeservedly unscathed, wiser, and resolving to carry a torch.

On another occasion, under jib and mizzen only, we were beating back to Arradon from the south-east in a stiff breeze made flukey by the wooded islands around us. Lacking the confidence to hoist the main we battled on, taking an hour and a half to cover the last mile. The final hundred yards through a crowded anchorage to find a vacant buoy were a desperate struggle under this reduced rig and oars; finally dropping back onto our buoy we ran it down sideways, its rusty top ring ploughing a furrow through our paintwork. With the addition of reefed main and a confidence we lacked at the time, I think we could have got Bunny back much quicker, under better control, and without recourse to the oars.

Bunny is a canoe yawl – there’s lots about them in TheCanoeYawl and Holmes of the Humber

Kicking & screaming

by Dick | 28 Jan 2023