My good friend Fabian Bush built me a (-nother!) boat a few years ago and we launched her together in 2014 at West Mersea in Essex. Teal is named for the ‘small dabbling duck’ in recognition of the direction my sailing was expected to take in my dotage, and she has proved to both sail and row beautifully. She is built in epoxied clinker plywood to the design ‘Aber’ by the Frenchman Francois Vivier, who has done so much to combine design tradition with modern developments in construction, and ease of use and maintenance. ‘Aber’ is the slightly slimmer sister of ‘Ilur’, a design sailed by many hundreds, including dinghy cruiser Roger Barnes whose exploits leave my occasional dabblings completely in the shade.

My good friend Fabian Bush built me a (-nother!) boat a few years ago and we launched her together in 2014 at West Mersea in Essex. Teal is named for the ‘small dabbling duck’ in recognition of the direction my sailing was expected to take in my dotage, and she has proved to both sail and row beautifully. She is built in epoxied clinker plywood to the design ‘Aber’ by the Frenchman Francois Vivier, who has done so much to combine design tradition with modern developments in construction, and ease of use and maintenance. ‘Aber’ is the slightly slimmer sister of ‘Ilur’, a design sailed by many hundreds, including dinghy cruiser Roger Barnes whose exploits leave my occasional dabblings completely in the shade.

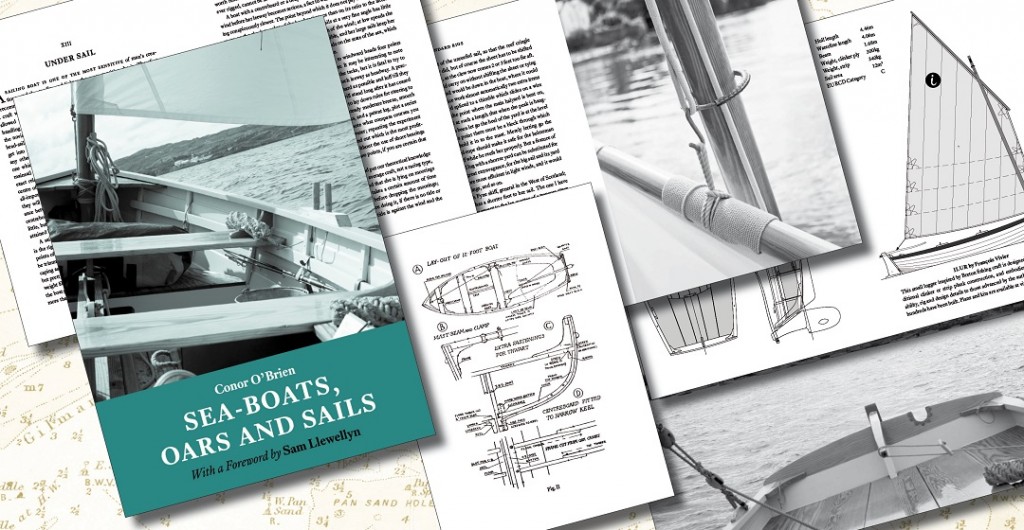

‘Aber’ and ‘Ilur’ are examples of the small lugsail dinghy advocated by Conor O’Brien in his pithy, opinionated, practical gem of a book Sea-Boats, Oars and Sails, which first appeared in 1940; to further inspire the reader we illustrated our 2013 edition with some glorious photos by boatbuilder and sailor Tim Cooke of his own Ilur, An Suire (The Sea-Nymph), operating in his home waters of south-west Ireland.

Here is how Conor O’Brien introduces his book:

Boats are of innumerable types, varying with their use and the waters they are used in, but within its own sphere each type of working boat is fixed. Not so with pleasure boats; their design changes at the caprice of fashions which follow racing practice, vaguely and often unintelligently, and each change increases their cost and their preciosity. These are times for realism, and nothing needs debunking more than the yachting and boating business. There are now many people, and there will be more, who would like to own sailing boats but are deterred by the supposed expense of the game and the suspicion that owners are not, after all, getting sea-value for that expense. But if they ask for a plain boat with no frills on they are shown some venerable relic with misfit sails and prehistoric gear, and they are warned off craft which may be entirely efficient and up-to-date, but do not conform with the latest fashion, by the horrible threat of being branded as unorthodox. Most of what is written about boats is naturally based on the orthodox view, and the man who wants a boat neither for class racing nor as a harbour ornament, but to go to sea in, gets little guidance from it. This book of mine is frankly unorthodox, in that I hold nothing sacred and take nothing for granted. I do not puff my wares with graphs and formulae like a quack medicine; if the reader does not accept my conclusions by the light of his own common sense let him reject them; I am no pontiff, merely a seeker after truth.

By a sea-boat I understand one that is a means of transport as well as something to go sailing in; one that will bring her owner to whatever place he wishes on any day when boats of the same size are out fishing. It may be as good to journey hopefully as to arrive, but a journey with not even the idea of arriving anywhere is apt to be boring; I at least have always enjoyed most those cruises which had a definite object. The boat must be fit for the journey in every way. The rules of the sea put safety first, and safety is best assured by simplicity of gear; the completion of the passage depends on speed, and speed is mainly a matter of size; the arrival in port must not be made anxious by qualms about a bad landing, as it will be if the boat is very costly and fragile. I must stress the matter of size, because the increasing cost of yachts and boats has reduced their size till they are only fit for the finest conditions and so slow that long passages are a penance or an impossibility.

In writing this book I have been guided entirely by considerations of practical utility, though I have not forgotten the old saying that no ugly ship was ever a good one, and I have tried out in practice most of the suggestions here made, before committing them to print. Chapters II-V show various boats as they are likely to be seen by a prospective purchaser, their construction, qualities, and the features I approve or disapprove of. Chapter II may be a deterrent to the amateur builder, but as there is more satisfaction in a thing made with one’s own hands than in one merely bought, and as some special types of boats, like the one described in Chapter VI, cannot be bought, and a home-made job, however crude, is better for very special work than a misfit, I give what I think is the easiest method of building, with workshop details. Other conditions, for instance, carriage on the roof of a car to exposed fishing water, difficult beach work, or frequent portages, require a combination of lightness and seaworthiness which is best exemplified in the curragh of the West of Ireland; that also cannot be bought, and as it is easy to build I give directions for doing so. Chapters VIII-XI overhaul all the equipment which may or may not be in a boat when bought or which may be bad and need alteration or replacement, and suggest some gadgets and fancy rigs for those with experimental minds. The last four chapters are on the handling of boats and general seamanship. Really bad conditions at sea are often passed over as things that do not happen to the amateur boatman; but he may be called upon at any time to save life. That call overrides all considerations of safety first, but if it finds him unprepared he may be an added danger to the man in distress. Our small boats cannot do much in the way of rescue work, but I have put together from instructions for larger boats what I think we might do, hoping that my readers may be able to amplify from other sources what I have written.

A book of 220 pages [as laid out in the 1944 edition] cannot cover the whole subject of boats. I have omitted many details of seamanship whose descriptions are easily accessible elsewhere or which are better learned from a study of the actual work. I have omitted the pram, whose construction is obvious, and whose virtues of lightness and cheapness are offset by her vicious behaviour under oars; also the dory, and all other craft with flat bottoms or angular bilges, for though cheap they cannot be light, as their form is inherently weaker than a round bottom, and it is also less sea-kindly, however well it may suit a speed-boat. I make no mention of full-powered craft, and I do not think an engine as auxiliary to sail is justified in a boat of the size I have in mind—not more than 25 feet in length and a ton in weight. I have not considered the question of racing at all. Class races are won on the windward leg, and go to boats of fabulous cost and limited utility for other work, but handicap races can be won by any boat which, though she may not be a star performer to windward, can keep up a high speed on a reach. This she will best achieve not with cast-off racing sails and gear, but with the rig suitable for her type, with sails well-cut and well cared for, properly stretched and set and accurately sheeted, and her hull trimmed truly to its marks. As races are often lost through slovenly sail-trimming, so they may be won by close attention to the smallest change in the force or direction of the wind, so that every inch of canvas is pulling its hardest all the time. With the rigs and with the gear which I advocate in the following pages, with a good helmsman and a smart crew, I claim that the sea-boat could, in her own weather, put up a very creditable fight against the more costly but less seaworthy craft which a mixed race gathers to oppose her.

But what of Teal? There have been distractions (read elsewhere here of Leona and Emerald). She now lives with my son on a sheltered inlet of the Baltic a few miles south of Stockholm, where she has drawn admiring looks from the local boating community. Getting her there was straightforward thanks to the roll-on, roll-off ferry service from Immingham, near Grimsby, to Gothenburg, which can take a boat and trailer unaccompanied, for collection on arrival. But a word of warning for others considering this method: You are not permitted into the cargo terminal at Immingham without high-visibility jacket and steel-capped boots; they don’t have these to lend you, so I was obliged to buy them on the day. There is a branch of the DIY chain Wickes a few miles away which will sell you them.

As I write this (December 2018) Sea-Boats, Oars and Sails is down to our last dozen copies. It has been one of our best and steadiest sellers; we may reprint it, meanwhile we have an e-book.

Teal, just completed

Teal, just completed