Despite its unprepossessing name Hole Haven, the creek to the west side of Canvey Island on the lower Thames, is a welcome bolt-hole for those bound up- or downriver needing to get some rest or wait out a tide. It has fulfilled this service since at least the 1890s (in the writings of Francis B Cooke and H Lewis Jones) and doubtless for many years before. I have overnighted here a couple of times in my canoe yawl Constance, and in time-honoured manner rowed ashore and visited the Lobster Smack inn just over the sea-wall on Canvey. Cooke warned of the perils of ‘boys’ in his day, and so, perhaps over-cautiously, we carried our tender from the hard to the inn with us.

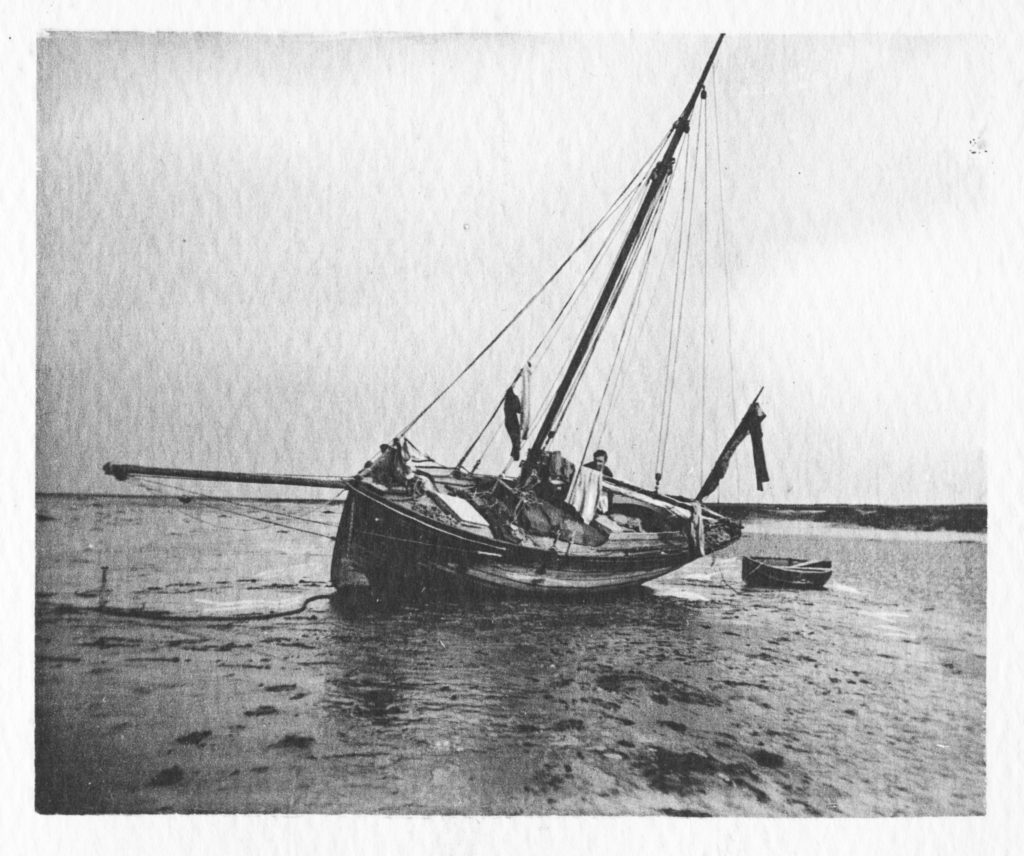

Henry Lewis Jones, a London physician specialising in the application of DC electricity to the body via a water bath (an idea which seems to have led nowhere), wrote Swin, Swale and Swatchway, a charming collection of cruising yarns which was published in 1892 and gives us a rare portal onto the cruising scene, and some aspects of shore-side life, of his day. It has been in and out of print since then, and was well ‘out’ when I tracked down a first edition at the British Library with a view to reissuing it with the best possible quality of illustration. I was delighted to discover that the book’s photos were printed in some continuous-tone, contact-print size manner not involving a halftone screen, so there was no fear of the dreaded moiré fringe effect in their further reproduction. Getting these copied at the BL was, however, prohibitively expensive and I resolved to find my own first edition, which turned up a year or more later, not cheap, but cheaper than the alternative. The book has a hard cover, covered in oilcloth, and with my copy this had got wet at some point in its history, but the interior has escaped wetting to remain, in the jargon of the trade, clean and bright with no foxing. The photos turned out well; the mottling effect visible in them is simply the texture of the paper they were printed on.

Here is Lewis Jones on Hole Haven:

Hole Haven is well known to most frequenters of the London river, especially to those whose headquarters are higher up, and there is generally a pretty show of small craft lying there on Saturday and Sunday evenings in the summer; indeed some yachtsmen seldom get any further down the river, and some do not get so far, for they stick upon the spit at the entrance, which runs down so as to form a regular trap for boats coming from up river. There are usually some picturesque Dutch eel boats lying moored inside; they find it a convenient harbour, because the eels which they bring over from Holland will not live long in the Thames water as it is found off Billingsgate, so they keep them here in reserve, and take them up to London when wanted. These Dutch boats moor in a tier off the Custom House, and form quite a feature in the view of the river from London Bridge, with their bluff bows, bright varnished sides and long pennants. Those who penetrate further into the Haven find themselves among hulks in which are stored gunpowder, gun-cotton and blasting gelatine in immense quantities. The solitary ship-keepers on these crafts are usually delighted to have a yarn, and will even invite you on board if they are satisfied that you are not “Magenta” (query Colonel Majendie), or some other inspector in disguise; and when on board they will regale you with thrilling accounts of the quantity of explosives which they have got stowed on board under your feet, or behind the stove, or beside the paraffin lamp, or, at any rate, in what seems to the unaccustomed visitor to be an unpleasant proximity to himself, until he begins to wish himself safe out of Hole Haven, and feels by anticipation a sensation of being propelled through space like a sky-rocket.

At low water Hole Haven is like a huge gutter with steep sides, and there is some risk lest a stranger should anchor on the edge of the shelf, and find himself at low water sliding down a slope of fifty degrees in a very awkward fix (there is less fear of this in that part of the Haven between the entrance and the first powder hulk than there is further up). We once escaped this accident more by good luck than anything else. It was at Easter time, cold, with a strong east wind, and when we got to Leigh and made a start, the sight of steamers brought up in Sea Reach waiting for it to moderate, together with a sample of the weather off Southend Pier, made us feel diffident about putting our noses outside into the channel. The tides were very good, so we determined to attempt the perils of the north-west passage round Canvey Island, and bearing up we came along past Benfleet in fine style, only sticking fast once, and that was near the entrance into Hole Haven; we got off again though, as soon as we had learnt from a rustic on the bank that the deep water lay on his side of us. In the afternoon, when the tide had ebbed, we walked round to view the scene of the grounding, and discovered our keel marks upon a salting, and the channel close by narrow and deep, like the gorge of a mountain torrent. After getting clear we soon came out into Hole Haven, which, as it was high water, looked like an inland sea, and keeping her close to the wind, we stood along the weather shore until we were opposite a powder hulk, when we resolved to bring up, but having espied a post sticking up from the water close to us, we sounded in four or five feet, and therefore let her blow off a little before letting go the anchor; soon we had no bottom with the sounding pole, so down went the anchor, amid frantic gesticulations and shouting from a neighbouring gunpowder ship captain. We could not make out a word he said, by reason of the strong wind, but he was trying to warn us not to anchor too soon; fortunately we were clear of the shelf, which must be at least twenty feet high at that place. How annoying it is to be shouted at by unintelligible people at critical moments. One feels that one is doing something wrong, may be suicidal; one feels that they know all about it, and are proffering the most excellent advice, and yet, after all, one has to act for one’s self and chance the consequences. When the tide had ebbed, we put on sea-boots and went for a visit to the powder hulk, and received a cordial invitation to come on board, which we did later on, and then we went and had a look at the river, and wondered what kind of weather we should have next day. It did not look very promising to see a great training brigantine labouring and pitching as she tacked down past the entrance to the Haven under a lower topsail, inner jib, and spanker, and we congratulated ourselves on being snug in harbour, and dolefully thought of the morrow, when we feared that we should be catching a similar or worse dusting on the way down to Sheerness.

Our worthy explosionist entertained us in the evening with the usual conversation, shouting out all his remarks at the top of his voice, even when we were sitting together in his tiny cabin. We thought he did this by way of practice, in order that when at length his cargo blew up, he might make his last words heard amid the crash of worlds. It is pleasant to take a walk on shore, and have a look at the island and the inn, with its quaint, low-ceiled rooms, which stand well below high-water mark. Here the rigours of sea cookery can be conveniently mitigated by a dinner on shore, for Mrs. Beckwith’s table is excellent, even if it be a trifle primitive. This inn seems to do a large trade for such a remote place; the front door opens into a low room with benches around it, on which sits rows of bargees engaged in a never-ending debate, each with a quart mug of beer in his hand, for they despise any smaller vessel. In the parlour is a very fine specimen of a visitors’ book, full of graphic tales of yacht cruises, and eke with illustrations. One would think from the logs therein written that the weather in these parts must be extremely stormy, for nearly every visitor has a tale, the good old tale, to tell of close reefs, heavy seas, cracking on and thrashing through, till one sincerely hopes that the mothers and fathers of the young and gallant yachtsmen may never see this visitors’ book, and learn how great are the perils of the stormy Thames.

Hole Haven is, I think, at its best in the evening, when all is calm and peaceful, and the tuneful Dutchman can be heard serenading the stars upon his concertina, smoking the mellow Canaster all the while. When ancient mythology comes to be rewritten, and brought up to date, and the number of the Muses increased to suit modern developments, then shall the Muse of Sea-song be drawn and represented with a concertina. Was there ever a vessel without a concertina in the forecastle? We feel sure that Orpheus must have had one when he went on that buccaneering expedition with the Argonauts, to say nothing of Arion and his music on the back of the dolphin. Even here, in smoky London, the concertina which goes along the street at midnight past my chambers calls up soft memories of one of Green’s good Australian clippers, and of balmy nights in the south-east trade wind, as she slipped along with all sail set, and the shreds of some ancient polka tuning up the while in the soft air of the first watch, and the Southern Cross . . . but there, my partner, who is nothing if not practical, is beginning to scoff, and wants to know who she was, and if I squeezed her hand!

A short distance from Hole Haven, on the island, there is a curious little round building, which is believed to have been built by the Dutch, who embanked and reclaimed Canvey Island, under the direction of Cornelius Vermuyden, in the time of King James the First.

In entering Hole Haven keep close to the east side, and if it is full of craft you can stand on a little way past the eel boats, and yet lie afloat at low water; this is a very good plan, unless one proposes to spend the evening ashore in the public-house, and wishes to be anchored near the landing-stage.

In going up to Hole Haven from below during the ebb, hug the opposite or south shore until reaching the Middle or even the East Blyth buoy, and then cut across, for the ebb runs very strongly to the last on the Canvey island side right down to the Chapman: a bit of a lesson which we learnt at the cost of three hours or so one Saturday night, when it was fine and calm, and we had crossed over from the other side too soon, and found the wind falling lighter and lighter, and ourselves drifting down and down to the Chapman. By the time we reached the north side we had been set down quite to the lighthouse, and the wind was all gone, and it was a case of out oars and row; it seemed as if the last drain of the ebb would never be done. Glad we were at last to find our bowsprit heading into the Haven, and to hear the rattle of the chain as we anchored in a snug berth, a hundred yards beyond Mr. Beckwith’s Inn. About midway along Canvey Island, between Hole Haven and the Chapman, there is a queer beacon on shore, looking just like a milliner’s lay figure; what its exact meaning is we have not been able to discover, although we tried to find out from a Coastguard officer at Hole Haven; he said it was a landmark for the purposes of navigation, but when pressed to say what its exact use was, he told us we would find it in the charts, and finally admitted, on further cross-examination, that he did not know what it was for.