For most of my life my sailing was of the armchair kind, and in the mid-1970s much of it was in the delightful company of Ken Duxbury, a writer whose light touch belies the skill and resourcefulness which underpinned the voyages made by him and his wife B. in their open 18-foot plywood Drascombe Lugger Lugworm, in the Greek islands, thence via the French canals and Biscay to England, and later by Ken alone sailing and exploring in Scilly and the Hebrides. Ken’s writing conveys that unique engagement with land and people which is achieved by approaching under sail in a small boat.

For most of my life my sailing was of the armchair kind, and in the mid-1970s much of it was in the delightful company of Ken Duxbury, a writer whose light touch belies the skill and resourcefulness which underpinned the voyages made by him and his wife B. in their open 18-foot plywood Drascombe Lugger Lugworm, in the Greek islands, thence via the French canals and Biscay to England, and later by Ken alone sailing and exploring in Scilly and the Hebrides. Ken’s writing conveys that unique engagement with land and people which is achieved by approaching under sail in a small boat.

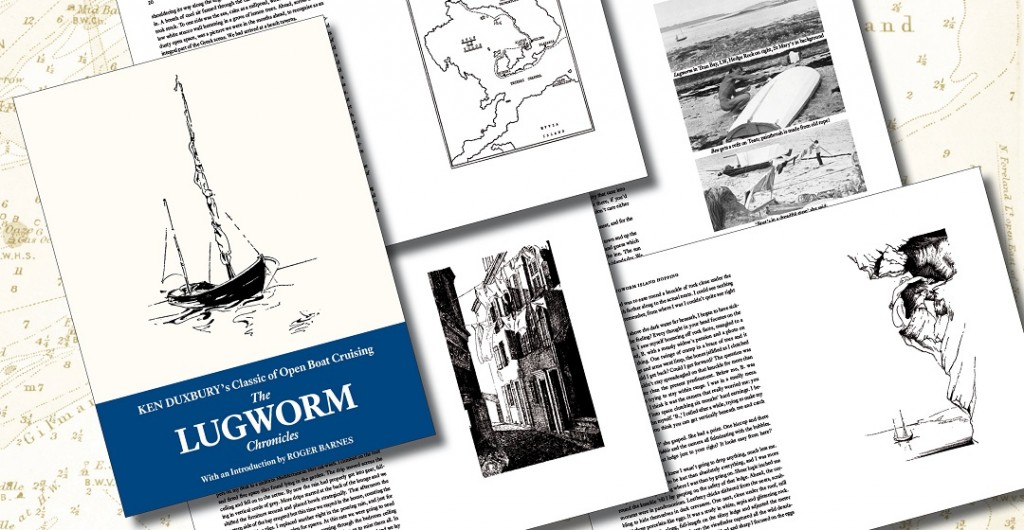

His three Lugworm books fell out of print, and commanded ‘silly prices’ secondhand; I resolved a few years ago to locate Ken (or his heirs) and see if we could get Lugworm before a fresh readership, and more affordably. A little sleuthing tracked him and B. down to their house on Bodmin Moor, where my wife Steve and I paid them a visit in which we all ‘hit it off’; Ken, in his late eighties considerably the senior partner, was bright as a button and thrilled that anyone remembered him and wanted to reissue his books. So this we did, as The Lugworm Chronicles—three bijou hardbound volumes in a slipcase of my own dining-table manufacture; this was mandated by the best estimate for its external production approaching the cost of printing the books themselves. Back then we were printing digitally in runs of 100 or so, and a reprint was soon needed. Two hundred and fifty sets shot out of the door at £36 before my excellent short-run printer ‘went under’ and I took the opportunity to review Lodestar’s production and distribution arrangements.

Whilst neither Ken nor I was a fan of omnibus volumes, it made a lot of sense at this stage of Lugworm‘s career to produce one, and so a 500-page robust, flapped, sewn softcover volume made its appearance in a run of 1000, for a ludicrously low £16; and with the move to higher volume, lower-unit cost litho printing, our books were now trade-friendly. Lugworm has been a steady seller for us and stock is dwindling. Sadly Ken died in 2016 at 92, but not before he saw both new editions of Lugworm appear, and could enjoy the entirely unanticipated royalties from them.

My son and I first encountered Roger Barnes at Morbihan Week in 2003, where we had taken our 15ft David Moss canoe yawl, and we were very impressed with his much smaller but well set up Tideway clinker cruising dinghy. We failed to catch his name but we did know from where he hailed and so, for some years thereafter, and encouraged by his only slightly shaggy appearance, we referred to him between ourselves as ‘Somerset Man’—something I disclose here for the first time, in confidence. Many readers will know he is President of the Dinghy Cruising Association, and I was very happy that he agreed to write an Introduction to the omnibus edition of The Lugworm Chronicles. Here it is:

Every mariner enjoys reading sailing stories, but sometimes the events described are so arduous and perilous that we finish the book hoping we may never experience anything similar—such as Shackleton’s small boat passage from Antarctica to South Georgia. But to my mind, the very best sailing books recount adventures we could easily imagine having ourselves. This volume is one of those.

Ken Duxbury and his wife took a standard Drascombe Lugger to the Mediterranean by road and spent the rest of the summer exploring the Greek Islands. The following year they sailed Lugworm back to England—across the Adriatic, along the Italian coast, through the French canals and finally across the Channel. It is an exciting story, but not an adventure hopelessly unattainable by the rest of us. No extremes of fortitude nor absurdly large amounts of money were required. The Duxburys took their time, making the voyage in short legs, rarely covering more than twelve miles a day. They wanted to explore the coastline, not to cover the mileage in the shortest possible time.

They made a point of seeking out the simple, ordinary and workaday. This is not a book about glamorous yachting. Apart from a brief foray to Monaco, where he failed to win on the gambling tables, Ken shunned the fashionable yachting scene. “If mankind had conspired to kill stone dead any last vestige of sea fever in his soul, he could not have devised a more effective means than his invention of the marina,” he writes. Instead Lugworm cruised between lonely rivers, isolated beaches and forgotten fishing ports.

Some readers may wonder if they would have been more comfortable in a small cabin yacht, instead of camping in the bottom of a centreboard dinghy. But that misses the point. Even the smallest cabin yacht would have restricted the places they could visit. The Duxburys could beach their boat almost anywhere, and then haul her out of the water with a block and tackle. They hugged the coastline, exploring virtually every bay and inlet, making many friends amongst the locals. A small open boat becomes part of the life of the coastline. Fishermen shared their catch, and gave them advice about what rivers were navigable; a Neapolitan chef sang as he cooked them pizzas.

I am writing this introduction while cruising my own dinghy around southern Brittany, meandering between the delightful havens and offshore islands of the Baie de Quiberon with a group of other small dinghies, rowing and sailing, camping ashore and afloat, and visiting a different restaurant in a different port every night: days of utter uncomplicated contentment. Only those who have experienced it know the true delight of cruising in a small dinghy. A certain austerity is enforced by the small space, but the blissful simplicity and freedom of the lifestyle rapidly becomes addictive. There is something almost monastic about escaping from the clutter of contemporary life. Ken Duxbury certainly valued this aspect of dinghy cruising. The final part of his trilogy of books, included in this volume, recounts his adventures around the British coast. Using his dinghy to live close to the seashore, he rediscovered an older and more authentic way of life, that of the longshore boatman and beachcomber. He fished for his food, collected firewood and even made a tender for his Lugger out of driftwood.

Ken is unfailingly plucky and resourceful. One of the generation who fought in the Second World War, he retains the laconic language of his Navy days—a rough sea is for him a “wetting sea.” His writing is humorous and vivacious, and illustrated with his own drawings and photographs. The drawings are a sheer delight: well-observed and economical. No one will reach the last page of his three books included in this volume without wanting to buy a small seaworthy dinghy and sail in the author’s wake—and why not?