By March of 1954 we had enough money for me to stop working and begin building in the farm loft. I cleared the chicken shit out, blocked up the gaps in the walls and levelled the floor. Building a small boat alone is like an exercise in meditation; throughout the summer I worked on my dream. The boat could have been built faster, but my father along with his head carpenter would occasionally visit to see my progress. This head carpenter was of the same ilk as the boat builders I had worked with at Thorneycroft. Each visit was like an examination.

On her days off, Ruth would come to sand, paint and put her feminine spirit into the boat. She was not the only feminine spirit; another young German girl, Jutta, visiting my English friends came to the boatshed and asked: ‘Can I help?’ To test her sincerity I gave her the unpleasant job of painting inside the small end hold. She did it without complaint. Then one day she said: ‘I would like to sail the oceans with you’. I knew that my planned voyage across the Atlantic on this small double canoe, to prove Thor Heyerdahl’s theories wrong, could be very hard and possibly very dangerous for a young outsider. Éric de Bisschop had shown that the double canoe was seaworthy, however his Kaimiloa was 38ft long; my little double canoe was only 23ft 6in. Éric had sailed thousands of miles across oceans even before his double canoe voyage. I was a beginner at offshore sailing and to encourage a young girl to join as crew was not sensible. I pointed out the hardships and danger that we might meet on the voyage. Her answer was: ‘I was in Berlin when the Russians came, I know and have seen hardships’. At that time the story of these wartime hardships and horrors was not generally known outside Germany. I did not fully realise what, as a girl of seven, she had seen and experienced. So I gave a grudging promise of ‘maybe’ and she returned to Germany.

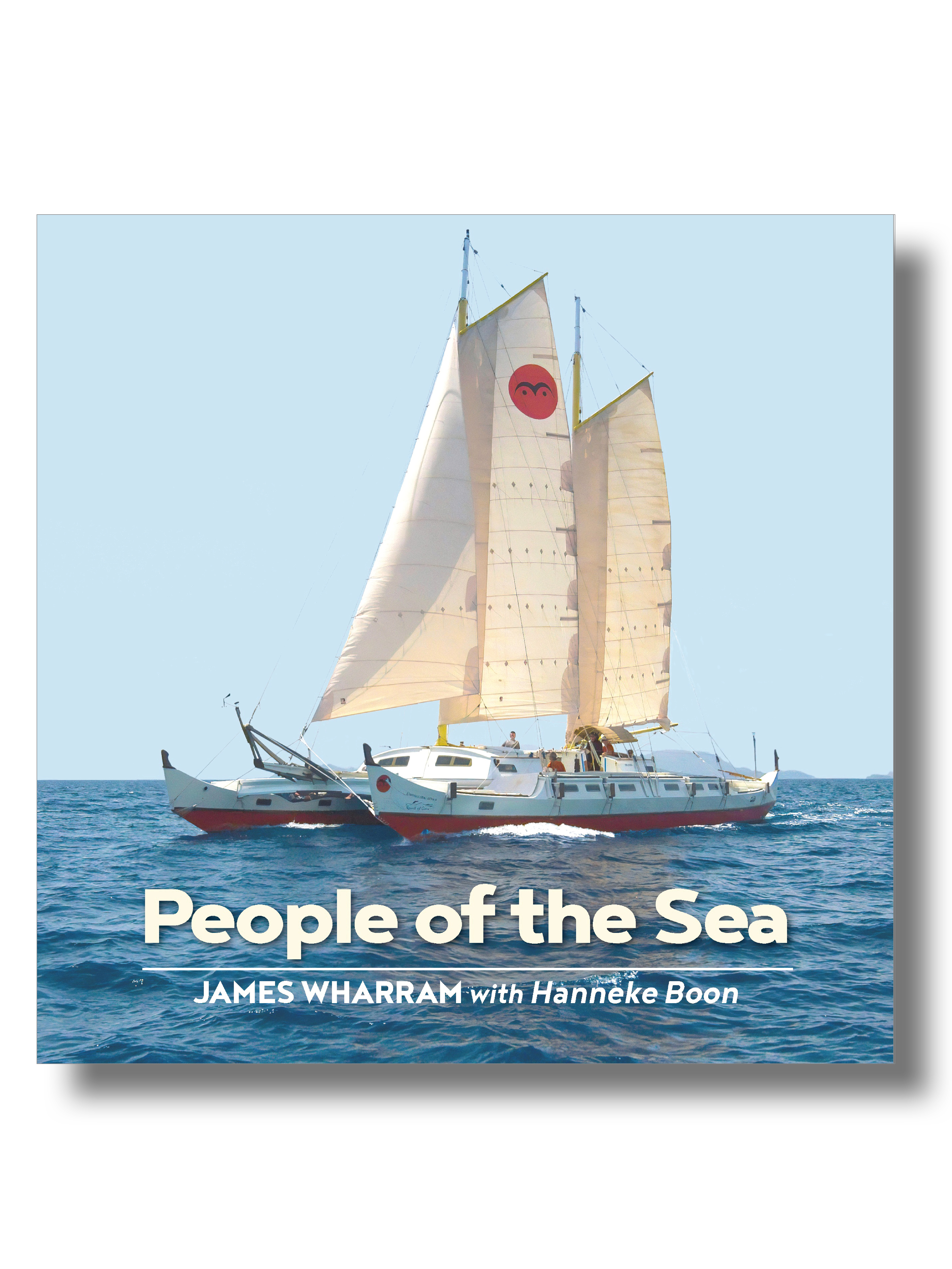

By September I had finished the boat in the barn loft, got it down to ground level without damaging the loft or the boat, and assembled the two red painted hulls, with their uniting beams on which I laid the slatted decks, into my darling little Tangaroa.

Compared to my adventurous hard living in the mountains, the accommodation on Tangaroa seemed luxurious. Others described it as living in two coffins, or more politely two wardrobes on their sides. I decided to launch Tangaroa on the Thames estuary. From Manchester to Burnham-on-Crouch in Essex was about 200 miles. Some young friends who were starting up in the building trade said if I gave them some help to finish a contract, they would load up Tangaroa on their lorry and transport the boat, Ruth and myself ‘free’ to Burnham.

We loaded up, collected our last gear from my parents’ house and said our goodbyes. Driving down the road I realised I had forgotten something and went back to find my strong, powerful mother weeping. Adventure for sons can be anxiety and sorrow for mothers. However I grabbed my forgotten gear, joined Ruth and my friends on the lorry and off we went. My building friends had a great time unloading the boat, assembling it and launching it. They drank the launching beer and sped back to Manchester to their next week’s work.

I climbed on board alone. ‘Hello Tangaroa’ I whispered. Ruth joined me. We looked into the hull compartments—no leaks! Next day Ruth and I together struggled to raise the tall mast. Still sweating we hoisted the sails, truthfully quite small compared to my later boats. Tangaroa ‘took off’, she leaped forward out of control; I had never experienced such rapid boat acceleration—and, out of control, we rammed her into a mud bank.

Dejectedly I hauled the sails down, bitterly thinking my design was a failure, and who was I to recover the lost art of Polynesian double canoe sailing? Ruth made me a cup of tea and began the woman’s job of rebuilding a man’s ego. Encouraged, we hauled off the mud waist deep in cold muddy water and tried again. This time Tangaroa tacked and tacked again—we had a sailing boat.

But it was late in the autumn and to sail down the English Channel and across the Bay of Biscay would have been tempting the sea gods. On advice we sailed up the River Colne to spend the winter in the waterside village of Wivenhoe, to get jobs and wait until springtime.

I have described how step-by-step I learned aspects of life, boat design and boat building. By chance Wivenhoe gave me my final study course in the attitudes I needed to become an ocean sailor.

Sailing up the river Colne we passed a tall shed-like building, behind which the village of Wivenhoe came into view. We spotted a simple wooden walkway over the mud, to which we tied up, and went ashore to a row of small cottages. One had the message ‘Notice—boats and gear stored at owner’s risk’ beside the door.

Out of the cottage came a small, alert white-haired man, wearing a peaked cap and a dark blue fisherman’s sweater, bearded with pipe in mouth. Bob Eves, eighty years old, was a retired legendary barge skipper who first went to sea at the age of twelve in 1886. He spent most of his life sailing flat-bottomed, leeboard, spritsail barges up to 80 feet long. Such sea craft were once a major transport system in the Thames and coastal waters. Their captains were men of legend.

Enquiring of him in his small living room as to whether we could moor our boat on his pontoon for the winter, we struck an immediate rapport. He later came to refer to me as his ‘Mate’. This was an honour. Ruth impressed him just as much, as he later told us she reminded him of his beloved late wife.

Ruth got a job in a small sardine-canning factory; I got a job in the nearby town of Colchester as machine moulder in an iron foundry, a job I had done years earlier when I had looked for my dream boat in Sweden. When both of us returned ‘home’ Bob would have kettles of hot water ready so we could wash off the grime and fish oil. Then would begin the discussions and reminiscences; from Bob I learned to think as a ‘Sailorman’.

Bob was not the only man of the sea in Wivenhoe. There was a solicitor in the village, John Donnelly, who in the immediate pre-war years had sailed around the world as bosun on a 118-foot engineless barquentine called the Cap Pilar. He was a traditional square-rigger ocean sailor. We used to babysit for him and he showed the concerned attitude of an older brother towards our sailing dreams.

Soon after we arrived in Wivenhoe, the cottage next door to Bob was bought by a tall, grey haired Mr Cully, as his retreat from a ‘somewhere upcountry’ wife and domesticity. He had been a judge in Siam—now Thailand—where, at the same time as the Cap Pilar was circumnavigating the world, he had a 45ft schooner built in the finest teak, from the board of the great American schooner designer John Alden. With a crew of four Malays he sailed her to Britain via the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, just before the 1939–45 war broke out. At that time not many yachts had made such a voyage. He made his at the same time as Éric de Bisschop was sailing his Kaimiloa from the Pacific to France via the Cape of Good Hope.

There was also a dear old man in the village called ‘Tiny’ (John) Howlett, being looked after by his devoted Chinese servant. I still have a copy of his book, Mostly about Boats.

All these men circulated around the Nottage Institute, set up in the 1890s to train local working boat sailors and transform them into professional yacht crews. There, during that winter, Ruth and I learned how to sew sails in the traditional method, stitching by hand. These experienced small boat sailors treated us as serious-minded pupils, indeed Wivenhoe at that time was a sea version of the early medieval universities I have described earlier.